When Bobbie Jarrett was in third grade, her class went on a field trip that included lunch at a Henderson restaurant.

But there was a problem, the executive director of the Housing Authority of Henderson told the audience during her keynote address at “A Night of Excellence” on Tuesday night at Henderson County Public Library.

Her teacher was told that the little girl could either eat in the kitchen or outside, but was refused service with the rest of her Holy Name School classmates.

Jarrett did neither. She went home and told her mother, who called her grandmother.

“Then the ball was rolling,” Jarret said, using this anecdote to talk about “three amazing women” — three unsung heroes — who came together to help a third-grade student.

“There would not be ‘me’ without these three people,” said Jarret, a member of the Henderson City-County Planning Commission, Henderson Leadership Initiative Board, Henderson Chamber of Commerce and many other community organizations.

“They were the ones who helped shape me and mold me. These three people came together at a time when I was at my lowest and that was as an 8-year-old child in the third grade.”

She spoke about them in honor of both Black History Month and Women’s History Month.

She said her first “unsung hero” was Florence Fendrick who was not to be denied when she went to the unintegrated Holy Name School to register two of her grandchildren and was refused.

Though Fendrick didn’t drive, this “woman of faith” somehow made it to Owensboro to visit with the bishop, whom she knew from working as a domestic at the Holy Name rectory and the convent.

After that visit, Jarrett said, all children of color were able to attend Holy Name.

“She had been laying the groundwork. She made connections. That’s called collaborative partnership and networking,” she said, noting that Fendrick’s two grandsons each ended up excelling because of the determination of their grandmother.

“We’re talking about being mentors and being excellent,” Jarrett said. “Just imagine if we would take the time to mentor to young men, young women whenever they fall by the wayside. Don’t let them fall by the wayside. Let’s give them a helping hand.”

Her second “unsung hero” was Annette Brown, who was an educator, poet and newspaper columnist, along with being an activist pushing for better pay for Black teachers and an end to segregation.

Jarrett remembers one summer walking by Brown’s house at the corner of Clay and Fagan streets and helping herself to a piece of fruit on the ground from one of Brown’s trees. Brown came out of the house, correcting her for not asking permission.

“I don’t know about you, but when I was growing up everyone in the neighborhood could correct you,” Jarrett said, and they could call your parents. Brown did just that.

That resulted in a punishment: She would spend the rest of the summer working for Brown on Saturdays.

But what she might have dreaded turned into something completely different. On her first Saturday, Jarrett was introduced to Brown’s Paul Lawrence Dunbar Literary Society. They learned things “we weren’t being taught in school” about Black writers and poets, the Harlem Renaissance and other topics. She learned the previously (unknown to her) Negro National Anthem.

“Miss Brown opened the door for Black History,” Jarrett said. “The punishment … was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Jarrett’s third “unsung hero” was Ora K. Glass, whom she remembers as a remarkable community leader and daughter of Rev. Paul Kennedy, pastor of First Missionary Baptist Church.

“Her contributions left an indelible mark on the educational landscape of Henderson,” Jarrett said of Glass, who pushed and advocated for the construction of Douglass High School, which was built on the Glass family land. Her efforts as a community leader got her an invitation to the White House from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

It was those three amazing women who got pulled into the conversation the evening after third-grader Jarrett was denied service during her school field trip.

She said they started meeting with community leaders like Dr. Anthony Brooks and Pierre Jackson to plan a demonstration, which was covered extensively in The Gleaner.

“These people went out on a limb for me,” Jarrett said, holding up a yellowed clipping from the newspaper that she has carried with her since 1961. “They went out and they protested. Dr. Brooks and Mr. Jackson went to jail.”

“I carry this paper with me as a reminder of the sacrifices that people have made for me. What those ladies did I will never forget, and I will try through the work that I do to level the playing field for those that I serve, for those that don’t have a voice,” she said.

In closing her remarks, Jarrett talked about some of the programs and services offered at the Housing Authority, where she has spent a 45-year career after growing up in public housing herself.

“Thank God for safe and affordable housing to live in,” she noted.

The housing authority has been recognized for excellence several times under Jarrett’s watch and offers senior programs, after-school programs, community health care, work-force development and home ownership programs.

It hasn’t always been an easy journey, but maintaining perseverance is a key to overcoming self-doubt and naysayers, Jarrett said.

She listed eight core values: Respect, trust, honesty, reliability, commitment, cooperation, flexibility and professionalism.

“A Night of Excellence” was a sold-out celebration planned for Black History Month and included a panel discussion about African American women in business/entrepreneurship with Alexa Hawes, Danielle Anguish and Jarrett.

Three excellence awards also were presented:

- Glenda Langley Dixon — Library Champion Award for her work in lifelong learning, reading and literacy

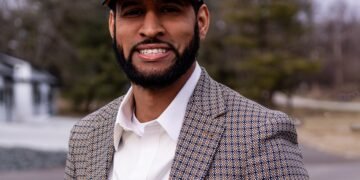

- Jarrett — Community Catalyst Award for “exceptional dedication, visionary leadership and profound impact on our community”

- Thomas Platt — Legacy of Leadership Lifetime Achievement Award for his work with the Black History Committee, local government and advocacy