(This article first appeared in the October print edition of the Hendersonian.)

No one died in building the 2022 U.S. 60 bridge over the Green River at Spottsville, but that marked a break in history’s pattern.

Bridges built there earlier, for both the highway and the railroad, were marked by the collapse of tons of steel–and the loss of lives. And that doesn’t include the lives that were lost in a 1904 train wreck.

The Louisville, St. Louis & Texas Railroad contracted with the Keystone Bridge Co. of Pittsburgh to erect the first bridge, which is downstream of the highway bridge. It was supposed to be completed by Nov. 1, 1888, according to articles in the Evansville Journal and the Evansville Courier, but work was delayed and the bridge wasn’t completed until mid-January 1889.

The Keystone company asked for final payment, but the railroad declined to accept the bridge; it said no further money would be forthcoming until it was compensated for the delay. The bridge company rejected that position, which prompted the railroad to get a court injunction allowing it to use the bridge. It placed six men at the bridge to guard its interests.

The afternoon of Jan. 20, 1889–four days before the railroad was to begin officially using the line–the bridge company’s superintendent, C.A. Cline, led a force of about 25 men onto the bridge. He grabbed the arm of T.P. Hapgood, the railroad’s superintendent of bridges, and spoke roughly to him.

“Get off of here, by G-d, you’ve been having a picnic here for two or three days; it is now my turn to have a picnic.” Hapgood asked what authority he had to flout the court order. “He said it didn’t make a d—m bit of difference by what authority, but if I didn’t get off quick, he would throw me off.”

Seeing his men were badly outnumbered, Hapgood said he would withdraw but with the understanding he was being forced off. “You bet you are being forced off,” Cline replied.

The railroad crossing at Spottsville is a drawbridge of the swing type; instead of lifting like more common bascule drawbridges, the main span pivots on the central pier to allow boat traffic to pass. Swing bridges are cheaper to build because the rail line can maintain a flat profile instead of having to build embankments on both sides. (Swing bridges also crossed the Green in McLean and Ohio counties, but the Spottsville bridge is the only one that remains functioning.)

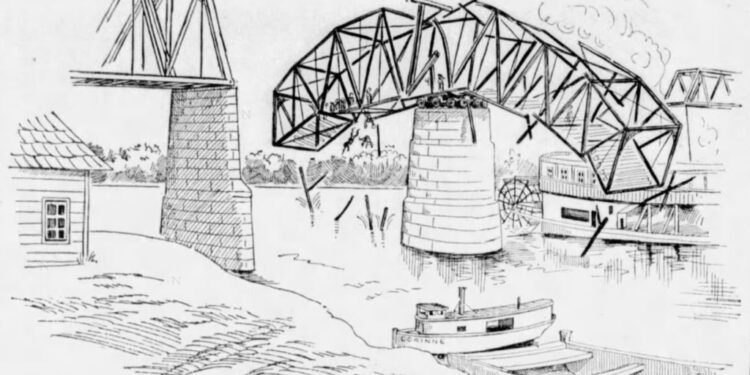

Once the railroad men had been ejected, the Keystone contingent swung open the span, started removing the rails and ties from the upstream end, and began throwing them in the river. They had stripped it and were headed for the much heavier downstream end when the overbalanced bridge broke in two and toppled steel, ties and men into the icy river.

Some men had sense enough to jump in the river and grab railroad ties when they saw the bridge tipping, about six or seven clung to the middle of the bridge, but others went down with the bridge.

The steamboat General Dawes had just passed under the bridge and escaped a much worse disaster by only a few yards. It immediately stopped and put out lifeboats. The tugboat Corinne and skiffs at Spottsville also were put to work rescuing those in the water.

Initial reports said 20 to 35 men had drowned, but only one body was found, although other men were injured.

As soon as he was rescued, Cline hopped in a buggy and fled the scene before chartering a skiff at the mouth of Race Creek and rowing to Evansville. The Evansville Journal of Jan. 26 reported he remained in hiding and had been indicted for manslaughter by the Henderson County grand jury.

The Keystone company rebuilt the span after settling the dispute; it opened to traffic March 11, 1889.

The “Texas” railroad, as that line was normally called, went bankrupt and was reorganized as the Louisville, Henderson & St. Louis Railroad in 1896. At 8:38 p.m. on Aug. 8, 1904, it had its worst train wreck at the Spottsville bridge when an eastbound freight train plunged into the river while the swing bridge was open.

The locomotive turned a somersault on the way down and was followed by about ten cars.

Newspapers differed on the names of the two known victims, the engineer and the fireman. The Courier and the Evansville Journal identified the engineer as Edward P. Riddle of Howell and the coal stoker as Lishen or Lisher. The Gleaner said Walter Riedel of Cloverport was the engineer and the fireman was initially Carl and later Wallace Lishen, also of Cloverport.

It’s unclear how many other fatalities there were. Evansville attorney George K. Denton was stranded all night at the Baskett train depot and at daylight he began walking to Spottsville to try to discover the cause of the delay. He saw the wreckage and talked to three miners who had been riding the freight to Owensboro. They had been in the last car dangling from the edge of the bridge.

One of them, his teeth chattering from fright, said, “I will never again attempt to steal a ride on a train. This has cured me.”

A hobo named J.P. Haydon was in the same car. He took it all as a matter of course, considering he was “soundly asleep” when discovered by rescuers searching the 10 cars that remained on the tracks.

The miners said two or three Black people had been riding in boxcars ahead of them and went into the river. Their bodies were never found. There were also reports of four white hobos who were never found.

Two of them might have been the other two bodies recovered. One had been mending umbrellas at the Henderson fire station the day before. In his pocket was about 18 inches of dark brown hair.

His companion, whose hair was that color, was wearing paint-stained overalls, in the pockets of which were typically masculine items such as a Barlow knife and Climax chewing tobacco. But she was not masculine–a fact that did not become apparent until she was being prepared for burial. “Sensational developments are numerous,” proclaimed The Gleaner’s headline.

She and the umbrella mender were buried in pauper graves at the county pest house after their identity could not be confirmed. No one prayed.

The bridge had been open because the steamboat Park City just passed through on its way upstream. “A few seconds earlier, that train would have hit the Park City, as she had just gotten from under,” said bridge watchman John Richardson. That would have greatly added to the loss of life.

There were five or six possible reasons why the engineer failed to heed the red warning light. “It is the supposition that the true cause of the wreck will never be known,” The Gleaner said in ending its Aug. 12 article.

The swing bridge was rebuilt in 1926 to carry heavier traffic. Before the construction contract was awarded the Owensboro Chamber of Commerce unsuccessfully tried to convince the railroad to design it to also carry traffic from nearby U.S. 60.

But U.S. 60 had to wait until the end of 1931 to get a bridge at Spottsville. And that construction project also proved deadly when the uncompleted span collapsed about 5 p.m. July 8, 1931.

The accident dropped four men into the water along with tons of steel and wood, according to articles in The Gleaner and the Courier. Vernon Hinton of Morganfield was the lone survivor of those four.

The three fatalities were Pat McCoun of Nashville; J.W. Flynn of Houston; and William Meinikheim of Mt. Vernon. McCoun and Meinikheim were badly mangled and died almost as soon as they were pulled from the water. Flynn died four hours later.

The accident came as no surprise. Wood braces that held the steel in place during construction had loosened earlier in the day and frantic efforts were being made to shore up the structure before it collapsed.

The falling bridge churned huge waves that capsized a boat containing seven men, three of whom were state Highway Department employees, but they swam safely to shore.

The Henderson Evening Journal published an extra edition, which prompted an estimated 3,000 people to visit the scene the evening of the accident.

Like the earlier accidents, it could have been much worse, according to The Gleaner. “Had the accident occurred five minutes earlier in all probability about 30 or 35 men would have been plunged to their deaths or serious injuries, as all but a few had just gone onto another section of the span before the collapse.”

The old Spottsville bridge took a fourth life before its dedication Dec. 17, 1931. On Oct. 16, Pearl Ligon of Beals was hit in the head by a block of wood accidentally dropped by another worker.