(This article first appeared in the November print edition of the Hendersonian.)

Abram Tyson was captain of a snagboat—one of “Uncle Sam’s tooth-pullers”—and played a significant role in opening the Mississippi River basin to steamboat traffic. He also was the only Henderson County slaveholder to be killed by one of his slaves.

Rivers were the equivalent of this country’s interstate highway system for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. That’s why many major cities in the eastern half of the country were built on waterways.

Many of Henderson’s most successful businessmen of the early 1800s made lucrative—but difficult and dangerous—trips in flatboats to New Orleans, where they sold their cargos and the timber in the flatboat, and then either walked or rode back to Henderson. Steamboats changed all that.

David Prentice, the man who built the steam engine for John James Audubon’s mill, did some warm-up work in 1815 by installing a crude engine on a keelboat, which he then chugged up to Pittsburgh in 1816. It was called the Zebulon M. Pike. In the summer of 1817, it was the first steamboat to visit St. Louis.

The Pike, like many early steamboats, had a relatively short life. It sank in the Red River in Louisiana in March of 1818 after hitting a snag. I’ll revisit the Red River when I delve into the life of Tyson, the focus of this column.

But first I need to tell you a bit about Capt. Henry M. Shreve, the namesake of Shreveport, La., and the man Tyson worked with closely for much of his river career.

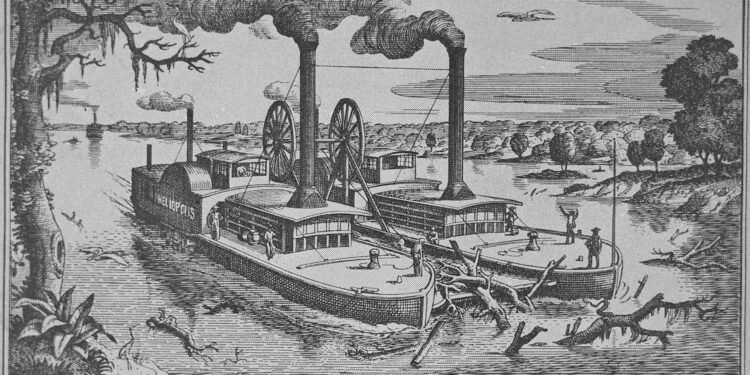

Shreve had three big accomplishments in his life. First, he demonstrated upriver travel was practical by steaming from New Orleans to Louisville. Second, he broke the monopoly on steam travel in the Mississippi basin. Third, he invented the first successful snagboat, the Heliopolis; snagboats made river travel safer and more profitable. It’s not an overstatement to say he ushered in the golden years of the steamboat era because he began serving as superintendent of Western river improvements in 1827, a job he held until 1841.

“Construction of the first snagboat was begun at New Albany, Indiana” in early 1829, according to a 1971 thesis written by Margaret Jean Furrh at Texas Tech University. “Shreve was assisted in construction of the vessel by Captain Abram Tyson and Captain John Dillingham.”

According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers website, during “America’s steamboat era, the main danger to waterborne travel and commerce was neither fire nor explosions, but rather snags—trees that had fallen into the rivers as a result of bank erosion. The current carried them to the center of the stream, and the heavier end, that with the roots, became lodged in the riverbed with the other end pointed downstream at an angle. A snag could punch a hole in a boat’s hull, often causing it to sink.”

The Army Corps website goes on to describe the Heliopolis, which “was a twin-hulled craft with an iron-sheathed beam, called a butting beam, connecting the hulls. To remove a snag, the vessel rammed it with the butting beam, dislodging the snag and allowing the crew to lift it onto the boat with a windlass. There it was cut up, the pieces to be used as fuel or thrown into the water to float harmlessly downstream.”

The Heliopolis was put to work on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers on Aug. 29, 1829. It was 112 feet long and each of the twin hulls were 17 feet wide. Another snagboat, the Archimedes, spearheaded Shreve’s goal of clearing a nearly 200-mile-long tangle of driftwood in the Red River called the “Great Raft.” It had accumulated over eight centuries and in places the obstacle was dozens of feet thick and had large trees growing in it.

People called him crazy for tackling such a job, but Shreve was ecstatic when five miles was cleared the first day of work in 1833, according to Edith McCall’s article in the winter 1988 issue of Invention & Technology magazine.

But the job wasn’t finished until Feb. 15, 1839, which opened up huge tracts in northwestern Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Shreveport, founded at the uppermost end of the “Great Raft,” was at one time the United State’s westernmost city and was the jumping off place for thousands of pioneers heading west.

Tyson, at the helm of the snagboat Eradicator, assisted in helping clear the “Great Raft” at the end of 1838. He was also captain of the snagboat Hercules on the Mississippi toward the end of his career.

But information about Tyson’s career or his early years is hard to come by. His gravestone in the historic North Cemetery in Mount Vernon says he was born Dec. 6, 1797, but his first appearance in Henderson County records was when Eliza Langley became his wife Aug. 29, 1834, at the Methodist Church in “Hendersonville.”

The next time he appears was when he and Capt. John Dillingham bought 206.25 acres on the Ohio River on April 22, 1844. Dillingham, his longtime colleague under Shreve, sold his interest in 1846.

Shreve retired in 1841. I’m not sure when Tyson hung up his captain’s cap, but I know he remained master of the Hercules as late as the spring of 1845. Newspaper accounts of his 1849 death refer to him as a former snagboat captain. A reprint of the account in the Louisville Journal noted he was a former resident of that city.

There are no existing Henderson newspapers from 1849 and there is no mention of his murder in the Evansville papers from that period. So, I’ve had to glean through accounts of other papers to get details about his death. In almost every case, they’re reprints from still other newspapers.

The Weekly Memphis Eagle reported Aug. 30, 1849, that Tyson had been shot by an enslaved man named Philip. “It is said that (Philip) previously threatened that if his master sold his wife, he would kill him.” The night of the sale he entered the house, obtained a double-barreled shotgun and fired it through the window at the sleeping Abram and Eliza Tyson.

The first shot missed but prompted Eliza to flee to safety. The second shot hit the captain in the lower part of his body.

The Vincennes Gazette of the same date reported Tyson was “an old and much esteemed citizen of Henderson County … whose residence is almost within view of Mount Vernon.” The buckshot took effect “in the captain’s leg, just below the knee, fracturing the bone badly and tearing away a large portion of the flesh.” He bled to death within 30 minutes.

The story noted Tyson had commanded snagboats on the Mississippi River system for many years. “He was universally esteemed for his kindness of heart and gentlemanly bearing, and from his almost proverbial forbearance with his slaves no one would have anticipated for him so tragical an end.”

A slightly different take was published in the Nov. 9 issue of The Liberator of Boston, William Lloyd Garrison’s leading anti-slavery publication.

“It appears that (Philip’s) wife and himself were slaves of Captain Tyson, and that the (wife) became so unmanageable that her master had to sell her. This exasperated (Philip) so that he threatened to murder his master and mistress, and accordingly,” the night of Aug. 20, 1849, he got a shotgun and killed Tyson, although Eliza Tyson “fortunately escaped. The murderer made no attempt to escape and was immediately taken into custody.”

The Memphis Daily Eagle of Nov. 13, in reprinting the account of the Henderson Kentuckian, reported Philip was hanged Nov. 2 “in the presence of an immense concourse of people who had assembled to witness the awful scene. Mr. W.H. Cunningham, in behalf of the prisoner, stated to the assemblage that the prisoner persisted to the last that he was innocent of the crime attributed to him.”

That execution took place, no doubt, in what is now Central Park, considering that’s where all other judicial hangings took place until the last one on Feb. 5, 1892.

The commonwealth of Kentucky paid Eliza Tyson $150 for executing her dead husband’s slave, according to court records.

The 1850 Census shows she was 35 that year and owned seven slaves, only two of whom were adults.

A paragraph in a May 18, 1851, letter in the Henderson County Public Library’s collection of letters by the Stites family leads me to wonder whether Eliza Tyson might have played a larger role in this tragedy than was reported in newspapers of the time. The letter is from Rebecca Stites to her son, Richard, who was a student at Centre College in Danville:

“We were very much surprised to hear of a wedding that took place in town a week or two ago—Eliza Tyson to a Mr. (Enoch R.) James of Mt. Vernon. He is said to be worth $100,000” because he was a banker. He also had five children, two of whom were grown. “I pity the three who are at home, for she has an awful temper.”