Part 1: Stories of those affected by the drug epidemic

This is the first of a 2-part series. In it, we talk to and listen to several people in our community directly affected by the drug and opioid epidemic. But make no mistake, there are many, many more who are struggling with some piece of the epidemic in Henderson. Without fail, every person who spoke to the Hendersonian shared their experiences because they want to save someone else from the horrors they’ve faced. If you know someone, or you are struggling with addiction, please find help. Check back next month when we examine what’s going on in Henderson to help and what else needs to be done in this epidemic.

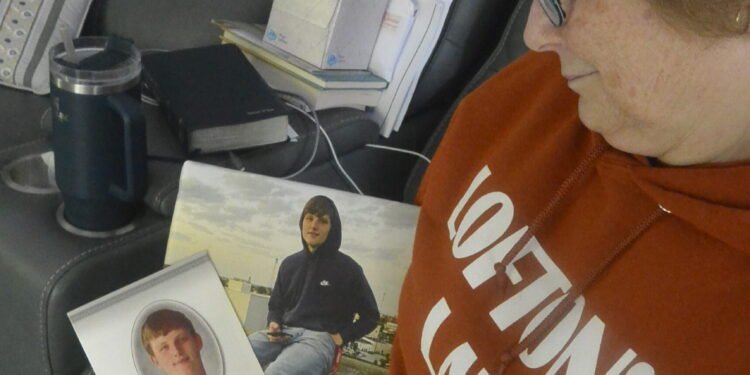

A mother’s loss

On Oct. 17, it will be a year since Gialene O’Nan’s son, Cash, died from a fentanyl overdose. Cash O’Nan was 17 when he died.

“It’s been a pretty tumultuous time,” O’Nan said. “It’s pretty tough.”

On the day of his death, O’Nan said she was at work in the emergency room at Deaconess Henderson Hospital when she got a text message at about 4 p.m. from her husband, Steve, who told her to call him immediately. “I think Cash is dead,” he told her when they spoke on the phone.

He wasn’t sure because the door of Cash’s room was locked, and O’Nan believes it had been locked since the night before, when he came home, talked to her a bit and then told her he was going to bed. He locked the door and took a pill, O’Nan said.

“He had probably died right after he’d gone to bed,” she said. “One pill can kill, and he got that pill.”

She was up early the next morning, unaware of what had occurred, and off to work, and Steve didn’t check on Cash until the afternoon when his son still hadn’t come out of his bedroom. When law enforcement and paramedics arrived, they were able to break down the door and confirm that Cash had died.

For Cash, life was grueling. O’Nan said her son was a great athlete and thrived on the field, but outside of sports, he struggled. Socially, he was awkward, and O’Nan thinks he was on the autism spectrum. School was hard. He had ADHD and couldn’t sit still. Learning was difficult, and Cash despised being there, O’Nan said.

Even though he was successful in sports, “He still didn’t think he was worthy,” O’Nan said.

In sixth grade, he got in with the wrong group of friends and started using marijuana. He spent the rest of his short life in and out of rehab and long-term juvenile facilities. Sometimes he was gone from home for 6-8 months at a time.

“We did everything in our power to see what we could do to make things better for him,” O’Nan said. “It just didn’t work.”

O’Nan has been a nurse for 38 years, in the ER for 23. In her line of work, she sees plenty of patients who’ve been using drugs. O’Nan said that with illicit drugs bought and sold today, users may not know if the pill is fentanyl or what percentage of fentanyl is in a pill. “You’re playing Russian roulette,” she said.

Some she sees only care about the next high, and some are ready to die. She said, though, that she didn’t think Cash was ready to die.

“God decided this is enough,” she said, adding that she is coming to some sense of peace about her son’s death. “I know this was God’s ultimate plan. I prayed every day for God to take care of my kid.”

Now, she said, Cash is in Heaven and taken care of. “I miss him every minute of every day.”

A father and son’s struggle

Andy Farris thought he was just making a quick stop at a gas station back in December 2020, when he ran into an old friend. The old friend happened to be someone he’d done drugs with and who also had a pill to give him. Farris thought it was an Oxycontin pill.

Andy, who’d been clean for a year at the time, didn’t think about the consequences, didn’t think about what he was doing. In fact, he didn’t think at all. He went to the gas station restroom, split the pill in two, ground up one half and snorted it. Then he drove home, less than a minute away.

At home he changed clothes and then lay on the couch, watching a football game with his father, Bruce, who at one point commented about a vicious tackle on the field. Andy didn’t answer. In that moment, he was overdosing about ten minutes after snorting the drug.

“The next thing I remember I was waking up in the hospital four days later,” Andy said.

The pill was, in fact, fentanyl. When Andy didn’t respond, his now fiancée, Amy, told Bruce she thought something was wrong—he wasn’t just asleep. Bruce resuscitated him and called paramedics, who used Narcan and got him to the hospital.

“That was the worst overdose I ever had,” said Andy, who said he has overdosed three times.

Addiction started for Andy, now 42, when he was 28. He was wrestling with a buddy when he tore his ACL. He was prescribed what he termed Roxycontin, which he said was pure Oxycodone and a very strong pain medication—one of the strongest.

His addiction after that pushed him to find pain pills for years as he bounced from job to job, never holding down anything good. He argued with his father when he was around and was always asking his mother, Cynthia, for money so he could get drugs. He found others who gave into his manipulations. He stole.

Bruce, a retired teacher, coach and administrator at Henderson County High School, often wouldn’t let his son in the house. And that hurt his wife, Bruce said, because it went against every bit of her maternal instincts.

“I just didn’t trust him,” Bruce said. He bought a safe to keep his money and any type of prescription medicine in.

“I was a piece of sh** son,” Andy said. “I know how much that hurt my parents.”

But undoubtedly, for Andy, his biggest regret and shame is what happened to his daughter, Karson.

Andy said Amy, who is also now in recovery, found his drug stash when she was 7 ½ months pregnant. Amy had been clean during her pregnancy, but she wanted to use.

“I allowed her to use so I wouldn’t have to stop,” he said.

His daughter was born addicted to opioids. In an interview with the Hendersonian, he said this shame he’ll take with him to the grave, and he began to cry.

“That was the lowest point in my life, for sure,” Andy said. “They say there’s a rock bottom in addiction. That was my rock bottom.”

Bruce said because neither Andy nor Amy had a driver’s license, he had to drive them to see Karson in the NICU unit after her birth. And it took everything in him to do it.

Fourteen days after Karson’s birth, Andy and Amy went to jail, and Karson, after leaving the hospital, began living with Bruce and Cynthia. Andy’s sister and brother-in-law, Katie and Josh Kirkwood, have also been caring for Karson.

Karson, now 4, is currently not in custody of Andy and Amy. They hope to take custody with continued sobriety. Karson has no effects from the dependency she was born with, both Andy and Bruce say.

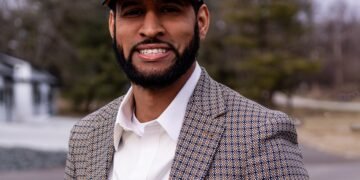

For the past two years, Andy has been clean. He credits his mentor, Aaron Brown, at the Men’s Addiction Recovery Campus in Bowling Green (which is under the same umbrella as the Women’s Addiction Recovery Manor in Henderson) as a rock that has helped him stay strong.

He’s making strides to regain his standing in life. He’s working in Bowling Green as a targeted case manager for Journey Pure, an addiction treatment center with branches in several states.

“I get my high now from helping someone (stay clean),” he said.

Last spring, he visited Henderson County High School health classes and shared his story with students while also educating them about fentanyl and other drugs.

Two years clean, he’s also recovering his relationship with his father.

Bruce said that there were many times throughout the years that he didn’t like his son. But, he said, he always loved him.

After years of distrust and anger between the two, Andy said his father is his best friend now.

“Our relationship is so much more than I thought it could be,” Andy said. “I was afraid I’d never get that back.”

WARM Center: Two in recovery look forward

Katie Johnson was 13 when she first smoked meth. Her teenage years, as she struggled through addiction, were hell on earth.

That battle ended, or was stopped, when she was 19.

Christmas presents wrapped under the tree, she was about to let her son, Cainen, who was 2 at the time, open one early.

Though she was high, she remembers the exact moment—3:14 p.m. on Dec. 6, 2021—when a unit of the Pennyrile Narcotics Task Force kicked in the door. The horror of her son’s face and his crying is seared in her memory.

And Cainen, now 4, still can also remember that moment, Johnson said, and it tears her up inside.

Johnson, from Muhlenberg County, was sentenced to 16 years in prison for trafficking drugs and subsequently taken to the Ross-Cash Center in Fredonia, where she stayed for six months. She attempted to get shock probation two times and was denied. On the third attempt—on day 180—it was granted. As part of the probation, she was sent to the Women’s Addiction Recovery Manor. That’s where she’s been since.

Johnson, 21, graduated from the 10-month first phase at WARM and is now working at the Recovery Resource Center of Henderson. She’s also a resident of the sober-living apartments that abut the WARM center.

Her life was turbulent when she began using drugs. Her parents, who’d been married 21 years, were divorcing and provided little oversight, each spending time with new love interests. Her father moved away.

For Johnson, a boyfriend–a 19-year-old man–filled the void. She said it’s creepy now to think about the age difference, but then, as a 13-year-old, she didn’t think so. She was just glad to be with someone who showered her with attention.

So, when he gave her meth, she didn’t say no. “It took off from there,” she said.

As the addiction progressed, so did her difficult life. She slept in a variety of places, bouncing from drug houses to boyfriends’ places to public park benches.

At 15, she found out she was pregnant.

“When I found out I was pregnant at 15 and I was in full-blown addiction, that was scary,” she said.

Another moment that she has a hard time forgiving herself for occurred when she was five months pregnant. She was smoking a meth pipe when she looked at herself in the mirror, and the shame she felt was instant, seeing herself using and knowing a living being was inside her. But she couldn’t stop.

“I knew I was hurting my baby but that’s what drugs do to you,” she said. “I hated myself.”

“Why can’t I stop?” she thought. “It didn’t matter how hard I wanted to stop, I just couldn’t.”

Johnson said she’ll stay in Henderson. She doesn’t know for how long, but she can’t go back to Muhlenberg County. She needs to stay away from the people she knew, she said.

“Everyone I know down there is on drugs,” she said.

She’s beginning to re-form relationships with her parents, though it’s still difficult. She thinks about how her life would be different if they’d been around in her teen years—“if they’d been there to tell me what to do”—but she’s trying to let those thoughts go.

She wants Cainen to live with her. She’s nearing that goal. She’s completed the required substance abuse program and a parenting class and now she’ll need to live in an apartment that has a separate bedroom for her son for at least six months before she can be eligible to regain custody.

Part of her recovery last year was to speak to students at HCHS. She’ll do that again this year. She said she gets real with students.

“When I talk to them, I try to be as raw as I can,” she said. “People are dying, here in your hometown.”

She talks about her own addiction and what she’s gone through, what her young son has been put through. She talks about a friend whose heart stopped for 12 minutes before she was resuscitated and given Narcan, and her son’s father, who can no longer function regularly because of his drug abuse.

“All the horror stories need to be shared,” she said.

*

Sarah Nicholson’s perception of an alcoholic was a guy with a bottle in a brown bag living under a bridge. Not her. Not a girl from a well-to-do family with a college degree who had started her own business.

Nicholson, 39, went to Indiana University and drank and partied there. She continued to drink through her 20s. She drank a lot, sure, but it was all in good fun.

Ten years ago, though, something changed. Her father, a dentist who was 62 at the time, died from melanoma, and at about the same time, she started a business, which she ran from her home. It came with a lot of free time and a lot of time at home, and she drank.

She said it got to the point that she’d make a drink first thing in the morning. She had to have a drink to be able to leave the house. Sometimes she needed a drink so that she could concentrate enough to write an email.

Along the way she got arrested seven times on driving under the influence charges, once after she left her work office (after leaving the business she’d started).

“It’s embarrassing, but it’s part of my story,” she said.

From 2018-2020, she took part in drug court and stayed sober. “I relapsed the day I got out of drug court,” she said.

She said the time from 2020 until she came to the WARM center in April were the worst for her.

“I had to drink to function… to go to the grocery store,” she said. “I felt like I couldn’t do anything without it.”

Now, five months into her WARM center program, she said she’s more confident she can make it. Her relationship with God is stronger, she said. She knows she’ll need to attend AA meetings four or five times each week. And this time, unlike the past when she attended AA meetings, she’ll need to truly work the Twelve Steps.

In the past, she said, “I was going to AA but I wasn’t working the program.”

Her why, she said, is hard to find, and she may never have a clear reason for her drinking. She had a wonderful childhood in Petersburg, Ind. She was safe and secure. Her father was a dentist, and her mother worked at a bank. She didn’t want for anything. Some of the trauma that others have endured—and contributed to their addiction—was not a part of her life. “Life was never bad,” she said.

Her reasoning is that she has the disease.

“The brain is sick,” she said in describing addicts. “We have a period of craving and then the obsession kicks in.”

Nicholson said that people suffering from addiction feel shame, guilt, remorse and unworthiness.

“It’s a horrible disease,” she said, adding that those suffering should know they’re not a bad person, but sick.

“There is hope. There’s a way out,” she said. “Everyone is worth recovery.”

Parents of Addicted Loved Ones look for understanding, hope

Sitting in on a Parents of Addicted Loved Ones meeting, it’s quickly evident how addiction turns the lives upside down.

Attendees’ testimonies illuminate the negative emotions they battle each day: fear, anxiety, worry, frustration, anger, shame, grief, and exhaustion—both physically and mentally.

“His drug of choice is meth,” one says, “and it’s scary.”

Another recalls that her loved one started using alcohol and heroin at 17. Now at 34, he’s been sober for 10 years.

Another says she’s in the middle of it right now. Both her daughter and granddaughter are using fentanyl, and they don’t want to quit.

A couple says their daughter has hit rock bottom and they’re trying to find any way they can to help her, including getting law enforcement to serve a Casey’s Law subpoena to put her in a recovery center. And then, they’ll at least know where she’s sleeping.

There’s more: a 21-year-old son whose drugs of choice are marijuana and cocaine; a husband who was clean for a while but has relapsed on cocaine; a 41-year-old who uses heroin; a daughter who battled alcoholism for 18 years; a 61-year-old who does cocaine; a 14-year-old who does fentanyl and meth and has overdosed seven times.

It’s also plain to see that addiction follows no rules. It strikes across socioeconomic lines, racial lines, age lines and neighborhood lines. It doesn’t discriminate.

And what’s finally evident, after all the worried stories are spoken and the negative emotions are released, is that two more powerful emotions remain: hope and love. That’s why they’re here.

They love their children and hope, sometimes against hope, that their children can find their way to sobriety and stay there.

Sometimes it’s a bewildering journey for parents in this situation, especially when instinct tells them to help the child, give the child some money so he can eat, pay the child’s rent so she has a place to sleep. But that’s not help, it’s enabling, which is what they discussed at a recent PAL meeting at the Recovery Resource Center of Henderson. It enables them to get high again. And again.

Enabling and how it’s different than helping was the focus of that meeting. It’s a tough distinction for the parents and loved ones to make. Sometimes their maternal or paternal instincts get in the way. And sometimes their addicted child finds a way to manipulate them to get what they want so that they can get high again.

It’s a rollercoaster journey for the parents and loved ones. They come to PAL meetings because they know they’ll meet others in similar situations, and they’ll find support for the choices they’ve made—right or wrong—and a non-judgmental environment because a fellow parent has been in the exact same spot.

A precursor to the local PAL group started about two years ago, when a group of six mothers, women who grew up in Henderson and raised their children here, began meeting once a month to talk about their sons and daughters who had been battling addiction for ten, 15, 20 years.

In a group history and mission statement they created, they wrote they were overwhelmed, scared and often hopeless, but they walked away from those early meetings filled with love, understanding and support given by the other ladies in the group.

They began researching and found the national PAL group, contacted them, reviewed the organization’s materials and went through training to become facilitators.

On May 17, Debbie Dempewolf, Bonnie Gelke, Cherry Liles, Cynthia Farris, Becky Hennessy and Sally Waller conducted their first local PAL meeting.

Dempewolf said parents and loved ones of a person struggling with addiction need to find a support group, which could mean others besides PAL, like Al-Anon or many others available in Henderson.

She said that when some of them needed help 10-20 years ago, there wasn’t anything available.

In the group’s founding story and mission, they write:

“We know that the drug problem in our community is on the rise. We know families in our community who are struggling with a child using drugs or alcohol. We know families that have lost a child to an overdose. We know that addiction is a journey for the whole family. We knew we wanted to do something in our community that could help other parents in a way we had helped each other.”

*

Out of respect for privacy, the Hendersonian only used names of PAL participants if permission was expressly granted during the meeting.

If you’re interested in PAL, meetings are 6-7:30 p.m. Tuesdays at the Recovery Resource Club of Henderson, 437 First Street. Contact the local PAL at 270-212-0116.

For help, call:

Recovery Resource Club of Henderson, 270-212-0116

The Women’s Addiction Recovery Manor, 270-826-0036

The Men’s Addiction Recovery Center, 270-716-0810

CORRECTION

In the October print issue of the Hendersonian, we reported incorrectly that Elijah Lovell supplied Cash O’Nan with the pill that led to his overdose death. In fact, prosecutors charged Austin Jenkins in connection to O’Nan’s death, according to Commonwealth’s Attorney Herbie McKee. The Hendersonian strives for accuracy in all our reporting. We regret the error.