(This history column first appeared in the January print edition of the Hendersonian.)

You could have a cougar next door and never know it.

But probably not. The website of the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife flatly states in bold type, “No evidence suggests that Kentucky is home to wild mountain lions.” Any seen hereabouts would most likely be an escapee or released captive, although Kentucky banned them as pets in 2005.

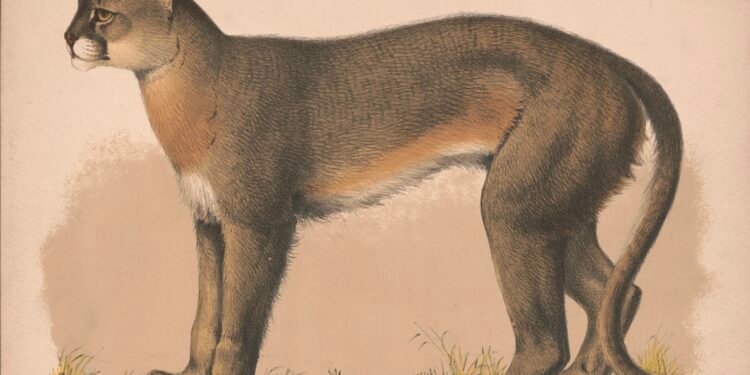

Mountain lions—also known as cougars, catamounts, panthers or pumas—once ranged all over North and South America. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says the Eastern mountain lion had disappeared by the 1930s and was officially declared extinct in 2011, except for a small population in southern Florida known locally as the Florida panther.

Cougars are wide-ranging beasts and have healthy populations from the western United States down through most of South America. Young males scouting out new territories in recent years have been confirmed in Illinois, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas, according to the Wildlife Nomads website.

And there have been sightings from trail cameras in Kentucky. (See Brecca Mefford’s Facebook posting of Dec. 11 for an example.)

In fact, a Kentucky Fish and Wildlife officer killed an adult male on Dec. 15, 2014, because it posed a danger to a nearby residential community in Bourbon County.

They’re definitely dangerous—but primarily to deer. They can leap 23 feet straight up and 39 feet horizontally, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. That’s a handy skill for ambush hunting.

“Their extremely sensitive hearing helps them detect prey and avoid human activity,” according to the Wildlife Nomads website. “This elusive nature allows mountain lion populations to coexist with humans in overlapping habitats. In fact, many people live near wild cougars without ever seeing one.”

Cougars posed a danger when white settlers first came to the Tri-County area, according to E.L. Starling’s 1887 “History of Henderson County, Kentucky.” He wrote, “The hillsides and valleys were thickly populated with wild animals, such as wolves, wildcats, panthers, deer and very frequently a large bear would be seen.”

The Union County Advocate of Feb. 14, 1929, carried a brief history of the county, which said in the early years “sheep were often devoured by wolves and panthers.”

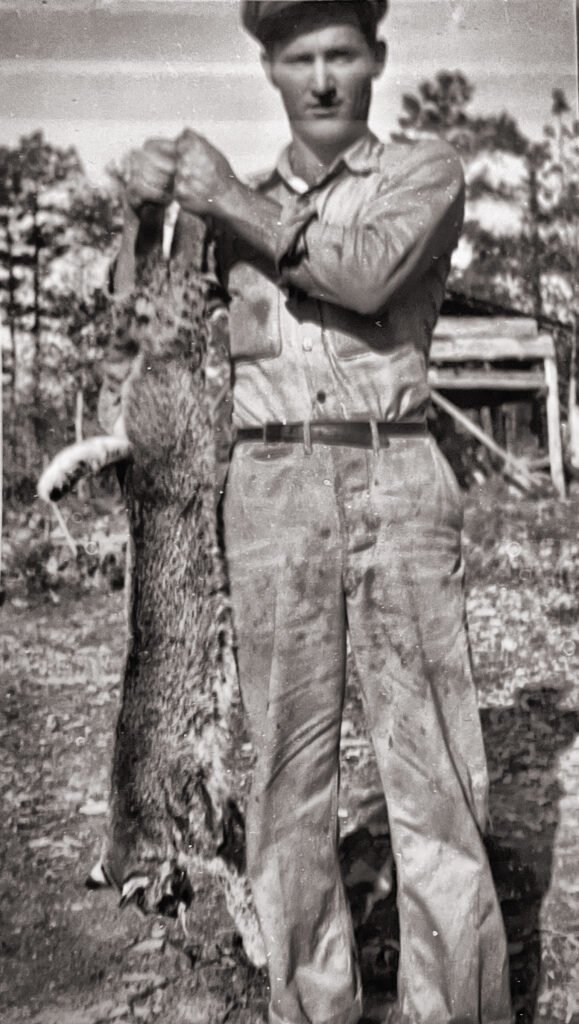

Y’all might be a trifle skeptical—as was I—about the veracity of some of the following newspaper accounts, most of which were left unresolved. A tendency toward exaggeration, fear or thrill of the hunt might have skewed perceptions of the reporting parties.

Take, for instance, three stories in the Evansville Journal that ran April 22-24, 1873.

The first story said a band of hunters had left Henderson to hunt for a panther seen near the covered White Bridge across Canoe Creek. Livingston Taylor and Nick Baker were among them.

The second story said the “terrible ‘painter’ —an old backwoods way of pronouncing panther—that that was prowling around seeking whom it might devour” had been anticlimactically killed. “The panther was a large red fox, that screamed remarkably like a panther. Thus ended the exciting panther hunt.”

The brief final story poked fun at the effort. “Mr. A.H. Talbott is the bloody hero of the ‘panther’ hunt, he having fired the fatal shot that laid the terrible fox low. Mr. George Payne is also reeking with glory, having shot a most villainous-looking owl.”

The early 1880s saw multiple reports of cougar activity. The Henderson Weekly Reporter of Nov. 22, 1881, apparently picked up on the story in the midst of the first excitement. “We understand another party went out in search of the ‘Panther’ Tuesday night. Our obituary pencil is ready to work on the first victim.”

Two days later the Reporter provided a longer story that gave more credence to the cougar talk, which had been circulating “for some time.” People began getting nervous after Thomas Dixon came back to town in his buggy with one-quarter of the top ripped away. Dixon said the big cat ambushed him as he was passing under a limb.

“An organized army of horsemen armed to the teeth went in search of the wild thing but failed to find it…. There is hardly a day, it is said, he is not seen by someone and his screams are hideous beyond contemplation.” It had been seen near the mouth of Sugar Creek.

An unnamed man said the panther had eaten at least one man and two boys, along with the equivalent of a small herd of swine, and the ferryman at the tip of Horseshoe Bend was losing business because people feared to travel in that area.

Edward Norris said he was walking along the road just beyond the Dade and Withers Distillery when the five-foot-long cat jumped from a tree and started after him. He fired several shots from his revolver. “I am sure I kinder stung him.”

Men with dogs rushed to the place where Norris had his exciting encounter. “They had gone but a short distance when the dogs returned with their tails tucked and refused to go further.”

The Nov. 29, 1881, Reporter said Rufus G. Cates had an encounter in the Frog Island flats. He later set out to kill the animal with a dozen dogs. “Being 12 to one they very soon dispatched him. He measured two and a half feet in length and weighed 30 pounds. Rather small for a panther….” (I suspect it was most likely a wildcat, which has a top weight of about 40 pounds.)

S. Epperson of Zion also killed a cat—but it was almost certainly a wildcat, according to the Twice-a-Week Reporter of Jan. 10, 1882, in which A.D. Combs had a letter saying he had a lot of experience “with panthers and has never known one of them to have a tail shorter than the body.”

The paper in Shawneetown wrote about a panther in the Geiger Lake vicinity in Union County, which was reprinted in the Twice-a-Week Reporter of Nov. 2, 1883. It had badly frightened a woman out riding. “Her husband laughed at her fears and rode out to see what was the matter. He was confronted by something like a panther and was glad enough to return without any tussle with it.”

Posey Marshall and Henry Rudy were going down to investigate but the Reporter didn’t carry any follow-up story.

The Gleaner carried a couple of stories in August 1931 about Sheriff Robert C. Soaper’s attempts to allay concerns of people in the Geneva area. “Discovery of the tracks and hearing the screams has caused considerable excitement,” causing multiple farmers to start packing guns to their fields as a precaution, according to the Aug. 18 edition.

“I have never seen such tracks before,” the sheriff said after investigating. “I believe it is either a mountain lion or a bear.” Bears don’t emit hair-raising screams, however, and cougars retract their claws when walking—much like domestic cats, which are their close cousins—so claw prints don’t appear in their tracks.

The Owensboro Messenger reprinted that story the following day and it recalled a February 1922 incident in which huge tracks (seven inches across!) were found along the banks of Yellow Creek. Plaster casts were made and sent to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. “A report was returned that only an African lion would leave such prints.”

The Gleaner of Aug. 20 carried a follow-up story about Soaper’s plans for a hunt with dogs owned by Oscar Letcher and Dr. R.E. Douglas. No one had seen the animal at that point. And apparently no one ever did, because The Gleaner said no more on the subject.

Henderson County had another cougar scare in April 1958. Charles and Mary Wright were living on U.S. 60-West about where Henderson Community College is now located. They first heard screams the night of April 2 but didn’t report it to the sheriff immediately.

Deputy Clark Fisher went hunting it, according to the April 5 Gleaner, and found large tracks with claw marks as close as 60 feet to the house. State Trooper Forrest Teer arrived as Fisher was checking the tracks.

The Gleaner reported April 6 that the animal “for the past three nights broke the evening stillness with its blood-curdling screams.”

Charles Wright described them as “like a woman in hysterics—just moaning and screaming. At first, I thought a car had turned over on the highway and someone was dying.”

As the noise continued, he looked out a back window and by the light of a full moon saw a black shape about 100 feet behind the house. He loaded a gun and went out.

But he was too awed to shoot when he got a better look at the animal. “It was completely black and stood about three feet high. You talk about scared!”

Four people, with the blessings of the state and federal wildlife agencies as well as the county sheriff, planned to go out hunting the black beast that night, according to The Gleaner of April 11.

The well-armed group—with two 8 mm Mausers, a lever action .38-55 Winchester and an elephant gun—included Edward Brown, Jack and Sidney Nelson, and high school senior George B. Nelson Jr.

The April 12 Gleaner carried a front-page photo of those men, accompanied by four dogs, who were going out again with the addition of Edward Adams, Marvin Byrer and Henry Herode.

No progress had been made by midnight. And that was The Gleaner’s last word on the subject.