(This column first appeared in the January print edition of the Hendersonian.)

A new year is upon us and we’ll be celebrating the nation’s Semiquincentennial — the 250th anniversary of the founding of America by the Declaration of Independence.

Why, it seems like just yesterday we were celebrating the U.S. Bicentennial.

It was, in fact, a half-century ago. So time goes.

Back in 1976, I was one year out of high school with a head full of brown hair. In 2026, I’m eligible for Medicare and Social Security, and my hair is white. A lot more than that has changed, too.

Take telephones.

During the Bicentennial, most Americans had phones. Some of them were affixed to kitchen walls; others sat on desks and were plugged into wall sockets. A lot of them had rotary dials, though some folks had fancy phones with push buttons.

Those phones were so vital to life that every year, the phone company printed and delivered telephone directories with the phone number and address of every customer (except for a few who paid extra to have unlisted numbers) to every home and business.

In the unlikely event that you didn’t have a phone book, you could call 411; a woman would answer by saying, “Information.”

In 1976, you could dial a long-distance number directly, but most folks remembered when they had to dial 0 for an operator. The caller could specify that they wanted to make a station-to-station long distance call — which meant that if anybody on the other end answered, the caller would automatically be charged a fee regardless of whether the individual they wanted to speak to was available.

Or one could make a person-to-person call, which would cost even more, but only if the person the caller told the operator they wanted to speak with was available.

This option created an opportunity for a little larceny. If, say, a traveling salesman named Jack Clark wanted to let his wife back home know that he had reached his destination, he could dial 0, give the operator his home phone number and say he wanted to place a person-to-person call to … Jack Clark. His wife back home would answer the call and tell the operator, “I’m sorry, but Mr. Clark isn’t home.” The operator would terminate the call, the wife would know that hubby was safe in some Holiday Inn … and Mr. Clark would save, say, $3.45, back when $3.45 amounted to something.

You could even place a collect call, hoping someone on the other end would pay for it.

In that same era a half-century ago, one didn’t absolutely need a mobile phone (not that anybody had one) because littered all around were pay telephones — in airports, shopping malls, pharmacies, restaurants and other public buildings, outside grocery stores or in corner phone booths. There used to even be a drive-up pay phone on Elm Street between Fourth and Fifth streets.

Drop in a dime and you could call anyone in town.

That was America in 1976. And we thought it would be that way forever. Of course, we also thought there would always be Sears, Roebuck. Or Kmart. Or Pan Am. We thought there would always be drive-in movie theaters. And drug store soda fountains.

And entities such as RCA and Magnavox and Zenith that had TVs and other products in nearly every American living room and were real pioneering technology companies, not just warmed-over trademarks.

And Saturday morning cartoons on TV for kids. (To be fair, today you can watch Woody Woodpecker and Bugs Bunny cartoons for a couple of hours on Saturday mornings on an over-the-air TV channel called MeTV, which features programming from the 1960s and ’70s supported mostly by commercials for Medicare Advantage plans.)

Later, we thought there would always be videocassette or DVD rental shops (think: Blockbuster).

And a long time ago, seemingly in a galaxy far, far away, we thought there would always be newspapers.

Those were conveyances of all sorts of information that were printed and sold at newsstands and on corners by newsboys, or tossed onto subscribers’ front porches by kids on bicycles. Once, newspapers were so cool that Superman’s Clark Kent cover was being a newspaper reporter, which kept him plugged into the events of mythical Metropolis. That was back when a million conversations began, “Didja see in the paper that …”

And then, newspapers—local newspapers, especially, like the once-proud Gleaner — shrank and shrank until they more or less vanished.

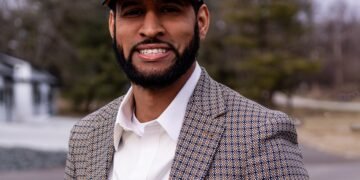

Then a couple of years ago, the Hendersonian appeared. It was the vision of one guy, Vince Tweddell, who had worked at newspapers at the tail end of their glory years … understood what they meant to a place like his hometown … and launched a new old-fashioned newspaper, available in print, via email subscription and online, with real Henderson news.

In 2026, that seems worth celebrating, too.