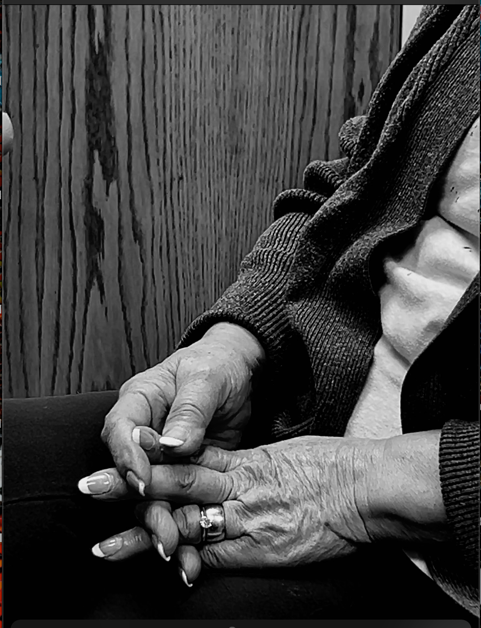

Hands are wondrous. They experience loving and unloving moments. They lift us, envelop us in comfort, most especially when they are our mother’s hands. Often they express what the mind and body cannot—when words do not readily arrive.

With the onslaught of dementia, one may find that hands begin to move more often, a kind of space filler, perhaps, when at a loss for a means of expression, or of remembering the verbal example of what we mean. Sometimes our hands quite literally complete our sentences.

Once, during a particularly difficult session at a speech therapist’s office, I found myself riveted by my mother’s hands. Impulsively, I pulled out my phone and began to film them—a kind of momentary reaction as they performed a nonverbal ballet. This was an instance when uncomfortable topics were being aired: the slide towards needing caregiver assistance, the inability to drive, etc. It was a tense interlude for me, and I couldn’t imagine what my mother was feeling. She is a lady, first and foremost, and culturally, still very Okinawan Japanese “mixed with Southern American.” When having to discuss such excruciating topics, she smiles politely and doesn’t reveal what is really going through her mind.

Her hands, however, are truth tellers. They glide, wring, pray, and punctuate the air when she agrees with the discussion, and more often, when she does not.

On this day, her hands are conducting a kind of silent opera revealing a story which begins and ends with her.

I feel there is a poignant correlation with the hands and dementia. According to The National Library of Medicine, “It has recently been reported that motor impairment can be detected in the early stages of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. We have conducted preliminary studies on finger movements in patients with dementia based on the fact that hand movements may detect pathological changes in the brain at an early stage. Accordingly, we detected finger movement features with cognitive decline; finger dexterity declines at Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment compared to healthy conditions. It is assumed that finger movements are intricately related to various brain parts and various aspects have not been investigated yet.”

According to the National Health Service in the United Kingdom: “Many people with frontotemporal dementia develop a number of unusual behaviors they are not aware of, including repetitive behaviors, such as humming, hand-rubbing, foot-tapping, or routines such as walking exactly the same route repetitively.”

Yet there remains a feeling of grace here. If words fail us as we enter into dementia and emotions are high, our hands lead us when our hearts, emotions, and memories may hurt.

Our hands, quite literally, are extensions of our selves. They are the extremities with which to tell our story – in any way that we are able.

My mother has fought many battles in her long life. This won’t be her last. She will always and forever be the hero in this tale she is telling. “Nana korobi ya oki”, she reminds me, when facing my own fragility. Translated from the Japanese proverb, it means “Fall down seven times, stand up eight.” This is a poem to all struggling with dementia in their families.

Henderson native Ane Crabtree, a 1982 graduate of Henderson County High School, has been a designer in Hollywood for 35 years. She has created looks for shows like “The Sopranos,” “Westworld,” “The Handmaid’s Tale,” “Darren Aronofsky’s Postcards from Earth”—the first film to premiere this year at the Las Vegas Sphere—and the recent, “The Changeling,” for Apple TV. She has also created designs for several shows of the futurist Liam Young.