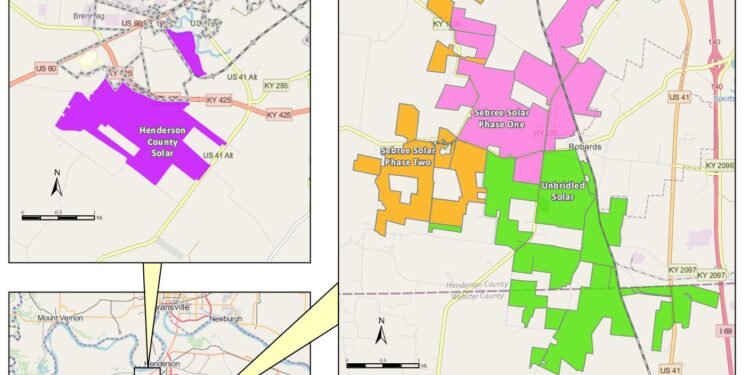

Fields of solar arrays are seemingly set to rise from the ground in Henderson County—541 acres straddling the 425-Bypass, some 3,800 acres in the Robards area and perhaps another 10,000 acres of reclaimed strip mines in the eastern part of the county.

And though they won’t be constructed for a year or more, landowners, residents, officials and farmers aren’t exactly certain what the county’s future landscape will look like.

Three projects are on track to begin. First, there are 541 acres on either side of the 425-Bypass, a project that Henderson Municipal Power and Light has worked with three different solar companies. The project is now being done by Stellar Renewable Power, said Brad Bickett, general manager for HMPL.

He foresees no roadblocks to getting it done and said the project will be complete by 2026, when the arrays will be collecting energy and transferring it to the city of Henderson’s substation #7 on South Green Street.

Another project is in its information-gathering phase. Rock Bluff Energy has set up two test towers to measure wind on reclaimed mine land near Hebbardsville owned by Penn Virginia, said former Henderson Mayor Steve Austin, who’s now working as local representative for Rock Bluff Energy, which is teaming with Tenaska and Cordelio Power, to get the project going.

Austin said the project he’s working on could possibly end up utilizing 50 wind turbines, each needing an acre of land. That will be determined after testing is complete in 18 months, but early indicators show that it’s a good possibility, he said.

Austin said the solar piece of the two-pronged project could entail 8,000 acres filled with solar arrays. He said, though, that the project is in the “very preliminary stages.”

Perhaps the most contentious solar developments have occurred around Robards, where two companies have secured contracts that together encompass some 3,800 acres. The Unbridled Solar project, led by National Grid Renewables, will take up about 1,700 acres, while Sebree Solar I and II, led by Next Era Energy, will comprise more than 2,000 acres.

Magistrate Taylor Tompkins, who represents residents where both Unbridled and Sebree Solar plan to locate, described the solar farms as “definitely a controversial subject.” He said his constituency is divided equally—half for solar and half against.

Several complaints have been raised in open meetings and on social media by those who’ve not signed leasing contracts with solar companies. They worried the solar arrays could be eyesores which would replace the idyllic country view they love so much.

Others aren’t convinced that climate change is happening and don’t see the need for renewable energy.

Still others have voiced concerns that properties located next to solar arrays would decrease in value, though that hasn’t proven the case in other areas, say solar companies.

But for some who’ve signed contracts, they believe they need to do something to help combat climate change. In comments at the Henderson City-County Joint Planning Commission meeting June 6, Robards resident Victoria Hust said she’s “aware of the impact the use of fossil fuels have had on the climate.”

Hust said she and others who’ve signed have engaged in the process and understand the intricacies of the deal. She also said she’s sensitive to the concerns of neighbors who didn’t sign contracts, but “we live in the area, too.”

Landowner rights are heavy in the minds of Magistrate Tompkins and Henderson County Judge-Executive Brad Schneider. Both said they don’t want to tell landowners what they can or can’t do with their land.

Schneider said the county has a solar ordinance, which puts in place guidelines to best appease neighbors who don’t want solar arrays near them. Recent Fiscal Court action, which came after a joint planning commission recommendation, approved an amendment to the solar zoning ordinance which had allowed solar development on land zoned agricultural. Now, land must be rezoned from agriculture to industrial or light industrial before solar can be built on it, a further action that could curb or slow down solar development.

Anything beyond having the ordinance, “it’s up to the landowners to do what they see fit,” Schneider said.

“Private land ownership comes with privileges,” Tompkins said.

Furthermore, farmers are cringing at the possibility of losing land to plant on. Local farmer Bob McIndoo said he’s recently lost the ability to work two plots of land totaling more than 350 acres because landowners signed contracts. He said he’ll lose gross profits of $351,000 and net profits of $140,00o this year.

“I’m adamantly against it,” McIndoo said, “but I hate to tell people what they can and can’t do with their property.”

Farmers’ leases with landowners don’t seem to compare to what solar companies can offer. Everyone the Hendersonian interviewed for this story agreed: The money offered by the solar companies is often too good pass up.

Schneider said solar companies are receiving big incentives from the federal government, which allows them, in turn, to pass big money on to landowners who sign.

The figures that McIndoo has heard are all over the place—upwards of $1,000 an acre over the course of 10, 20, 30 years. Other figures he’s heard include a starting payment of $50 per acre with increases occurring as development occurs, reaching the highest amounts—such as $1,000 an acre—once the solar arrays are up and running. It’s all hearsay, he said.

But any way you cut it, that’s a lot of money.

One landowner, Roger Brown, decided he didn’t want to deal with leases and any hassles that may have come with that. He and his family decided to sell. Closing last week after four years of talks and paperwork, Brown said he got 2 ½ times the value of what his Robards land is worth.

And then there are the farmers in the county who agree that solar needs to be a part of the energy equation, but they don’t agree with current locations, especially knowing that farmers will lose the opportunity to work valuable, tillable cropland. One is Robbie Williams, who is probably as much for the proliferation of solar energy as anyone in the county.

Williams, who comes from a long line of farmers in the eastern part of the county, has 270 solar arrays placed at four different locations on his properties. At his home, he produces 120% of the needed electricity. That means 20% of what his solar arrays produce goes back to Kenergy. (The county solar ordinance allows solar arrays on agricultural land if the area is not greater than one acre.)

Williams believes that people and government should be doing all they can to use renewable energy. That includes putting solar panels and arrays on roofs, hillsides, old landfills and reclaimed mine sites, like what could occur on the Penn Virginia site in Hebbardsville.

But not on good cropland.

“I think it’s just the path of least resistance,” Williams said of the solar companies’ plans to place arrays on farmland. “We’re looking at quick profits and desecrating good farmland instead of looking at the long term.”

Williams has helped to construct 34 solar arrays for other farmers and landowners in the county, he said. All are placed on untillable land. With a planet of 8 billion people who need to be fed and with good cropland at a premium, the choice is easy for Williams.

And then there’s another type of farmer in all this—the farmer who’s growing older, does not have the energy to continue farming his land and whose sons or daughters don’t want to farm. The farmer’s connection to the land he’s lived on and worked his whole life, however, makes it almost impossible to sell.

Tompkins said he’s worked with farmers in just that situation. So, to keep the land in the family, they’ve signed a solar contract which would allow the solar company to build arrays on the land, use the land to produce solar energy for the life of the contract, and once the arrays are decommissioned and torn down, revert the land back to the farmer, or if he’s not alive, his family, Tompkins said. Even those against solar have shown empathy to a farmer in this predicament, he said.

The idea of solar arrays probably wasn’t on the mind of many landowners 10, or even five years ago, when Robards landowners began getting letters in the mail from solar companies.

Tompkins, whose family owns 83 acres in the area, said he turned down solar company requests to lease their land. He said he was approached in 2018—before he was a magistrate—with a letter and then was visited by solar company representatives. Ultimately, though, he felt that the contract language left too much unanswered, he said.

When the push first began years ago, solar company representatives contacted and met with landowners in attempts to secure leases. Tompkins said residents in the area received a lot of misinformation early on, which caused confusion and anger.

Many talks and conversations have occurred since then, and after taking office Tompkins, said he’s been in the middle, working with the different sides of the issue and speaking to joint planning commission.

A June joint planning commission recommendation that would require agricultural land to be rezoned as industrial or light industrial before solar could be built upon it was passed to the Henderson Fiscal Court for a vote in July. The court approved it. Because Tompkins had been so involved with the process, he abstained from voting, he said.

The county solar ordinance also requires that equipment not be taller than 25 feet, that the solar arrays be 100 feet or farther from residential structures, that the equipment be 25 feet from the project property line, that solar equipment is screened by at least a 7-foot fence and a visual buffer of vegetative screening (trees) is present to reduce the view of equipment from neighbors’ homes or residences.

According to Schneider, solar farms won’t produce many full-time jobs. But the county will see property taxes increase on the land holding the solar arrays and that increase will come to county government, he said.

Bickett, the general manager for HMPL, says we are in the middle of the greatest change in energy in the past hundred years.

“We are at a time that’s the most significant change in the energy landscape since the electrification of businesses and households,” he said.

In the past, when using fossil fuels, utilities were able to load up on power, mostly coal, to meet the needs of an area. Going forward, the model is more akin to controlling the demand based on the generation that is being produced, Bickett said.

While that may not sound like the best option for customers, Bickett stresses that relying on past energy production, specifically fossil fuels, is more costly. There’s really no option to rely solely on fossil fuels anymore, he said.

Though coal is still a player in the game—just look to the construction of the new Henderson County Mine near Little Dixie that began this summer as proof of that—it’s not the only player. And Bickett said it’s one of the highest cost options, if it can be permitted.

He points to construction of new plants and upkeep of old ones that are too expensive for most municipalities, and the costly cleanup that coal plants leave behind. Bickett said HMPL is currently cleaning a coal ash pond left after Station #2 in Sebree closed in 2019. He said the price tag is $16.165 million. The share for HMPL, coming from reserve funds, is $3.05 million, Bickett said.

And so, it appears solar is here to stay. But what does that mean in Henderson County?

Joint planning commission staff say they’re still fielding calls from interested solar companies. But Brian Bishop, the planning commission executive director, believes the recent amendment to the solar ordinance calling for land to be re-zoned to industrial will cause solar companies to stay away. He said he doesn’t foresee more solar companies here in five years than those already approved.

In five years’ time, Tompkins said people driving through the Robards area will see fields of solar arrays mixed in with the corn and soybean fields. It’s assured, he said.

But will the solar companies live up to all the promises they’ve made to those who’ve signed contracts?

“That’s the great unknown and my largest concern,” Tompkins said. “Time will tell.”