(This article first appeared in the January print edition of the Hendersonian.)

The Great Depression was not only financial in nature. It also plunged multiple Henderson County residents to the point of despair.

Many of them were the same people who won World War II—both at home and abroad—but the war has largely overshadowed the Greatest Generation’s ordeal in surviving the 1930s.

Between 1930 and 1933 there was 36 percent deflation, which threw about one in four people out of work. Coal mines, banks and retail businesses shut down and major industries such as the cotton mill and Marstall Furniture Co. closed their doors.

But this column tries to focus more on the human side of the ledger.

In some ways, Henderson County was fortunate. The county was primarily agricultural, although the main crop was tobacco—which wasn’t particularly nutritious—but truck gardens and other crops could be grown and preserved. (The Gleaner of Nov. 22, 1931, reported at least 45,980 quarts of fruits and vegetables were canned locally in late 1931. The following year the federal government began distributing seed.)

But growing food carried its own problems. The Gleaner of Oct. 15, 1930, reported the watchman at the Ben Niles orchard near Cairo had fired at a prowler because “depredations on apple orchards has reached alarming proportions.”

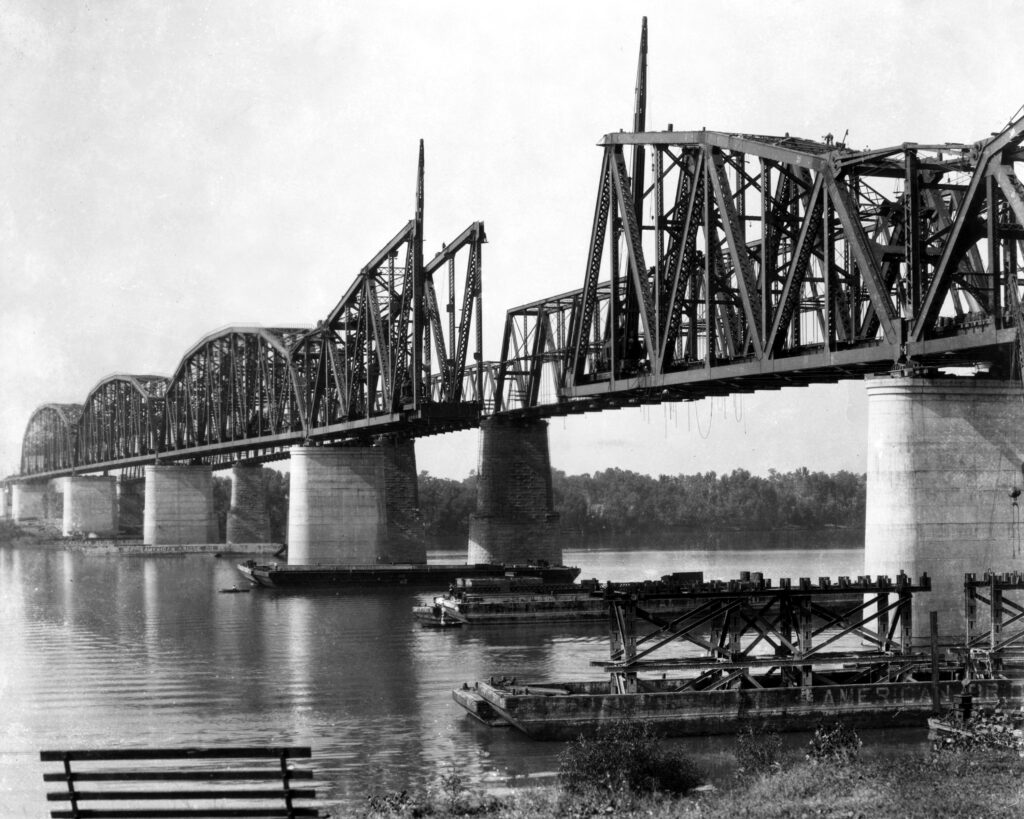

And then there was the construction of three major bridges in the early 1930s: the L&N bridge at the Henderson riverfront, a highway bridge over the Green River at Spottsville, and the northbound span of the Twin Bridges. The payroll for those projects pumped much-needed cash into the local economy.

But those projects also carried a downside, almost an attractive nuisance. W.G. Schoepflin, in his Gleaner column of Oct. 4, 1931, noted there had always been hobos riding the rails by choice. But as the Great Depression dawned, he wrote, many were looking for work “and becoming more and more depressed each day….

“Many of the trains carry as high as 25 men and they will probably average 10 or more per train. They used to make them get off the trains but not so anymore.”

In the same column he wrote about a woman with a baby at her breast, a boy about three, and a girl about 11 living in a boxcar at the train yard. Their only food came from what the girl could beg. He first noticed them when they came into his father’s nearby grocery with five pennies and asked for a nickel’s worth of sausage.

“They were supplied with food and milk. Only walked half a block from the store when they stopped and, resting on the rails, ate in such a hungry fashion that it made one feel such that you could not look on.”

Private charity and federal money initially helped alleviate the needs of the poor. During the winter of 1931-32, a total of more than 61 tons of food was distributed by Unemployment Relief to 375 households with jobless family heads as well as providing food to 363 children at seven public school kitchens.

All told, some 2,060 people—or about one-twelfth of the county’s total population—were fed with that food. They were kept warm with 107 tons of coal and the “considerable quantities of clothes” distributed. Much of that clothing was made and repaired by local churches. All the food and goods had been donated or bought with donated money.

Men heading those households had to work for that assistance, however. The Gleaner of Dec. 17, 1932, described the miserable working conditions. “It was bitter cold, and a cutting wind blew down the country lanes and roads and some of the men were poorly clad for zero weather, but they stuck to the job gamely.”

The cold weather caused the demand for “direct relief” to rise dramatically. That was the issuance of coal and grocery orders without a work requirement. Dr. W.I. Markwell, head of the local Unemployment Relief office, said shoes were the greatest need after coal. “Scores of children in the public schools are need of shoes.”

The city and county governments felt the pinch almost immediately as the Great Depression descended. In May 1932 Tax Commissioner W.P. Kellen reported that the total value of real estate in Henderson County had dropped from $28.4 million in 1931 to $25.1 million in 1932, a reduction of $3.3 million.

A big part of the problem for Henderson Fiscal Court was pauper claims. County Judge B.S. Morris told the court in the Oct. 9, 1930, Gleaner that pauper claims had been costing the county more than $30,000 annually. Two days later the judge was authorized to borrow money to operate, although banks soon stopped extending credit.

That prompted fiscal court to begin issuing interest-bearing warrants to pay its debts. The county did not get back on a cash basis until mid-1935.

The city of Henderson was in the same shape. Throughout 1931 the city jail was often filled to overcrowding with people simply looking for a place to sleep. The Gleaner of March 22 reported 540 had been registered since Jan. 1. The Gleaner of Jan. 28, 1932, noted 702 “sleepers” had stayed at the jail since Nov. 27.

Schoepflin’s column of Sept. 16, 1931, depicted the jail after midnight as “nothing so interesting and yet so sad.” College-educated men looking for work, as well as “women with children not knowing where the next meal will come from.”

The city jail apparently stopped accepting “sleepers” in early 1932 because there was no further mention of them after Jan. 28. And the city began experiencing a severe cash crunch.

In the fall of 1932, about 30 city employees were fired, and all other employees saw wage decreases of at least 10 percent. In some cases, the pay cuts were as much as 50 percent. Those layoffs were rescinded in January 1933, although the net result was that all city employees saw pay decreases of 15 percent.

Franklin D. Roosevelt won 71 percent of the vote in Henderson County in 1932, the highest majority any presidential candidate had ever won here. The first “alphabet soup” agency created locally by his New Deal was the Civil Works Administration, although it was later superseded by the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, which built Audubon State Park.

Schoepflin’s column of Dec. 7, 1933, reported improvements when the first paychecks from the CWA program were paid. “The old uptown section did not look like the same place and there was more buying going on in Henderson than for three years or more.”

The WPA soon became the county’s biggest employer, however. When it shut down its works here temporarily in 1936—because a WPA officer had been roughed up—that halted all sewer work, street paving projects, work on the Audubon State Park museum and county projects. All told about 1,000 men were thrown out of work.

About the same time there were multiple stories in The Gleaner about people being cold and hungry, which prompted fundraising efforts but also sparked a fiery letter from Bob Sheffer that appeared Feb. 9, 1936.

“People have been living in the meanest shacks and even in holes in the riverbank for a long time,” he wrote. “If a person has only lately become interested in the relief problem, he leaves himself open to the suspicion that his noble actions are backed by a spirit of fear—fear that the suffering horde may suddenly turn mad and start destroying….

“If you assume the attitude that property is more sacred than life and attempt to maintain property by force, your property will be confiscated and your life treated as you would treat the lives of others. This is not a threat, but a solemn warning borne out by all past history. What are you going to do about it?”

Things were looking up, however. Major WPA projects built here in the late 1930s included Atkinson Pool, the Reed school and the county training school for Black students, about 160 miles of roads and streets, 69 new bridges and viaducts, the state park museum, the old log pavilion in Atkinson Park, the creation of a boulevard on North Elm Street, more than 12 miles of sewer line, and the rock wall on the riverfront between Second and Third streets, which many of you probably remember.

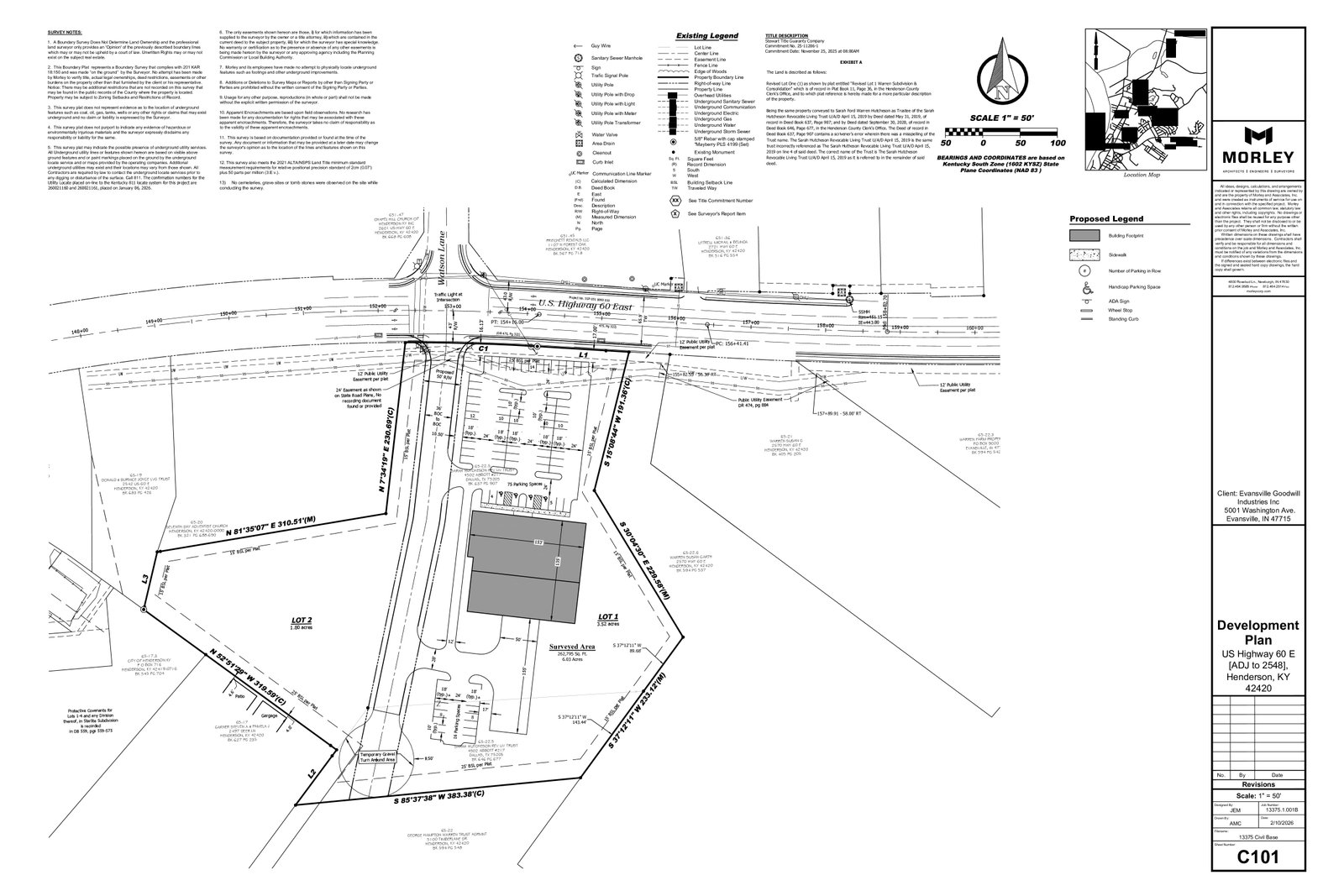

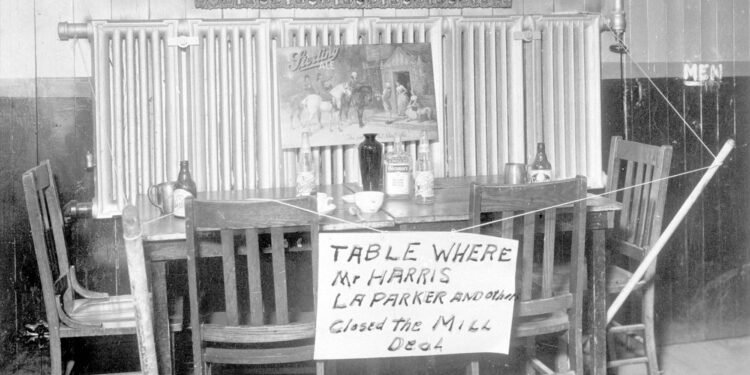

Things were moving on the private front, too. In May 1936, the Cornbleet Bros.’ Betty Maid dress factory opened, and the former Marstall furniture factory was in the process of being restarted. And through the efforts of Gleaner publisher Leigh Harris the former cotton mill—closed since 1931—reopened as the Bear Brand Co. sock factory on June 14, 1937.

No overview of the 1930s here would be complete without a mention of the great 1937 flood, although so much has been written about it that I’ll provide only a synopsis.

The flood of 1937 began with a total of 21 inches of precipitation falling between Jan. 5 and Jan. 23, marking a record for the most precipitation in one month. The river gauge crested at nearly 54 feet, which remains the record.

Henderson was the only sizable city along the Ohio River that did not have flooding within its city limits, which prompted an influx of numerous refugees. Multiple residents did praiseworthy work in helping them and in rescuing livestock from the countryside.