(This Black History Month article first appeared in the February print edition of the Hendersonian)

Starting at the river and going up Second Street, the businesses between Water and Main streets were predominantly black-owned and operated before World War II. On the south side in the middle of the block was Gaines Funeral Home with a room above for band practice (The band that W. C. Handy initiated). On the north side were two buildings owned by the U.B.F. Lodge, St. John’s Lodge and two dance halls, all patronized by Blacks. On Aug. 4 of each year, the halls were filled to capacity to celebrate “Emancipation Day.”

Going east on Second Street between Elm and Green was another black-owned building. Purchased by Dr. William Wilson and Peter Cabell, it housed a drug store on the first floor with offices on the second floor for a dentist, two insurance men, two doctors and a private clubroom.

The first pharmacist was Atwood Cabell (whose brothers Delma Cabell and Roger Cabell followed in the same trade in Providence, Bowling Green, Evansville and Louisville) and later a female pharmacist, Lillian Austin. Some of the Black doctors in Henderson, not necessarily in order, included: Drs. O’Neal, Armistead, Wilson, Weston, Davie, Gowdy, Watson, Downer, Beam, Pettit, Glass and House. Dentists were Drs. Glover, Irvine, Smith and Mason.

Another center for Black trade was in the vicinity of Alves and Dixon streets. Here were groceries operated by Woolfolk (Fellows) and Ware, a meat market by Langley, and in later years, the drug store. Scattered over town were other groceries operated by Redder, McClure, Aaron and George Cabell. Aaron Cabell bought the large estate of Jacob Held and it became Cabell’s Park.

Returning to downtown Henderson, the stroller found the Black barbershop, which also catered to white trade. The first was F.B. Doxey who opened up on the west side of Main Street, about three doors from First Street. Soon, Ben Taylor and Dallas Longley started barbering in the adjoining building to the south. If a visitor were lucky, he might find Ben Taylor working on a part for his handmade railroad train. When he stopped to clip a customer’s hair, he handed the part to his shoeshine boy, Lorenzo Jones, to finish sanding. The finished engine was about three feet long, steam-powered, and pulled flat cars. Displayed in the shop for a time, Taylor used it later to haul coal from his coal house to his home.

Doxey also built a theater on the front of his home to show movies to the Black community. This was on the lot later used for the old downtown Gleaner building, now a parking lot.

Pioneer in mechanics and electronics

Many people think “equal opportunity employment” was brought by federal edict. At least one Henderson employer was practicing it many years before any federal laws were written.

When Bethel Brown opened the Radio Sales and Service in 1926 on Seventh Street, he not only served both segments of the community but also trained young people from this and nearby communities. As the only warranted Motorola service repairman in the area, he—a Black man himself—opened his shop for training young people of both races. In particular, there was Stewart Henderson and Earl (Bud) Musgrave (who later became a doctor) both from Zion.

Brown was an early “Ham” radio operator, building his first set in 1918. He enjoyed talking with other “Ham” operators. His call letters were W4NUQ.

He was forced to retire in 1972 when the Board of Education took his building so that it could build Seventh Street Elementary School. His long-term employees June Simms, who joined the organization in 1949 as a salesclerk and bookkeeper, and Irving Briscoe, his serviceman for 30 years, both secured jobs with Anaconda Aluminum Company.

As a pioneer in the electronics field, Brown was following in the footsteps of his father, Joe Brown, who learned the mechanics trade at the first Ford garage in Henderson and then in 1916 established a garage and filling station, owned and operated by an African American. He was awarded a plaque by Standard Oil Company for having held the dealership for the longest time in the community.

At Brown’s first station, Tom Polk delivered fuel by filling up a barrel. Joe Brown had garages at the same location, Elm and Sixth streets. He kept up to date by returning to Detroit twice for additional training.

When Joe Brown had to retire from the garage business because of ill health, his son William Brown took over the garage adjoining Bethel’s radio shop. Joe became custodian at the Ohio Valley Bank and Trust Company, where he served until 1943.

Joe Brown had three daughters and he started early training them to work by establishing an “Auto Laundry” where they wielded the sponges and cloths for hand washing the machines. This was before the jet-propelled streams of water used today.

Rev. Austin Bell

The Rev. Austin Bell had been actively working with the unemployed and underemployed for many years before the government “Manpower Program” began. He served the Norris Chapel Baptist Church as pastor for almost 25 years and worked for both the physical and spiritual well-being of his people.

As early as 1950, he was invited to speak to the Henderson Lions Club and stressed the fact that no factory in the Henderson area employed Blacks. Immediately afterward, Elmer Korth conferred with Rev. Bell and opened a hosiery mill building on Holloway Street that employed an all-Black crew—supervisors as well as workers. This continued until it integrated with the Washington Street mill in the 1960s.

Many times Bell helped as a liaison between the Black and white communities, serving on a number of boards of directors, including the Chamber of Commerce, Henderson Community College and Henderson Hospital. He was the first chairman of the Board of Directors of the Henderson-Union-Webster Development Council.

In 1972, the Henderson Chamber of Commerce honored him as the “Distinguished Citizen of the Year.” In 1974, he was the recipient of an award jointly sponsored by the Community Action Program and Chamber of Commerce in Kentucky for his contribution to the Manpower Program in this area.

After his retirement as pastor, Rev. Bell continued to work with the Neighborhood Youth Corps and to teach two classes at the Hopkinsville College of the Bible, a school jointly sponsored by the National Baptist Convention and Southern Baptist Convention.

A Black newspaper

The Henderson Communicator, a weekly Black newspaper, was established on June 6, 1936. The Thompson family—Lewis, Leona and Mattie Thompson—published this paper every Saturday for more than 20 years. It was a useful means of communication for the Black community.

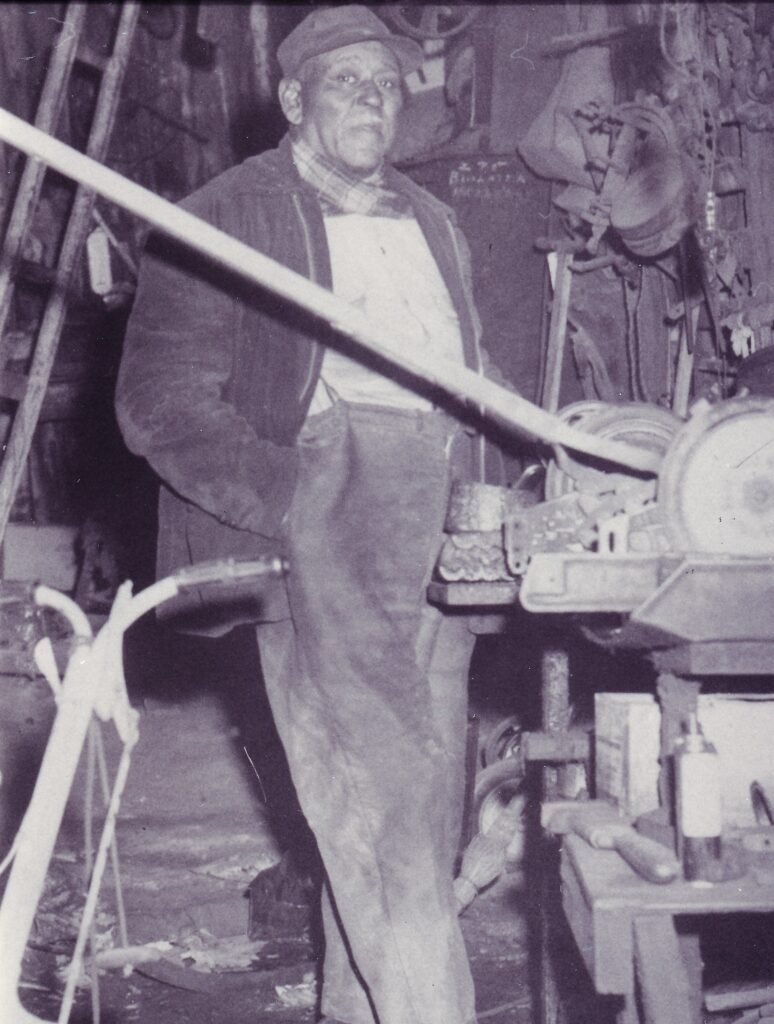

Blacksmith for nearly a century

When Sneed Brown closed his blacksmith shop on First Street in 1959, he was closing the last blacksmith shop, the city’s oldest business operating under the same name, and a family tradition of 93 years.

Mike Brown had started the blacksmithing business in 1866, six years after he came to Henderson as the slave of Mrs. E.G. Hall, the mayor’s wife. She did not treat him as a possession but permitted him to pursue his trade and keep the money he earned. When his savings reached $1,000, he was able to purchase the female slave he wished to marry.

Although Mike Brown earned his living by manual labor, he and his family did not neglect their minds. They read the classics, kept informed on current events and educated their children. Two daughters, Nellie Brown and Susan Brown, and a granddaughter, Annette C. Brown, became teachers. They were meticulous in teaching correct English (spoken and written) to their pupils throughout the day.

Mike’s son, Ed, worked with his father and learned his techniques in handling skittish horses and fitting iron shoes. He took over the trade and among his five children found one, Sneed, who was interested in learning the craft and continuing the business. Another son taught the art of shoeing horses in a Louisville school. Sneed Brown began working in the shop on the 400 block of First Street when he was 14 and continued for 51 years. At first, most of the horses brought to the shop came from the farms, later racehorses were brought in to be shod.

As machines took over farm work, the number of four-legged customers dropped to less than 50 a year. Sneed added the sharpening of tools and lawnmowers to his business. In 1959, he closed the shop and make tool sharpening a part-time business at his home, where he could relax and watch Westerns on television. Not that he found the plots interesting, but the blacksmith shops were.

Only eight months after his partial retirement, Sneed Brown died.

Donald Banks is a Henderson historian. He has published two books. He specializes in genealogy and does a lot of work in local history, especially Black history. He is also a U.S. Army Veteran, serving in the Vietnam War from 1968-1969. He was awarded a Purple Heart and two Bronze Stars. He is a member of the Honor Guard American Legion Post 40.