Strengthening relationships with a community is often a top priority for those at the helm of law enforcement agencies.

While this is true for the city’s soon-to-be police chief Billy Bolin, initially, he said, a different group is getting precedence—Henderson police officers.

“My biggest goal is to build relationships with people within these walls,” he said.

Hired more than a month ago, the almost 51-year-old veteran police chief said, “During my time here, I’ve been trying to get to know the officers, supervisors and the detectives. I walk around, pop into people’s offices and go to roll call—even the one at 6 p.m. I’m spending time talking to people about what they want from their chief.”

Bolin said the overwhelming feedback he’s receiving from officers is that “they just want to see their chief.”

“Some of the feedback I’m getting is they want someone who isn’t stuck in their office, but who is visible” Bolin said. “There’s a stairwell that leads straight out to the back parking lot and doesn’t go through the roll call room. I’ve had several officers tell me they don’t want to see a chief who ducks out the back door. They like it when the chief comes through the roll call area. So, I’ve made it a point to do that. I’m never going to go out that door without looping around first and talking to people.”

An active proponent of community policing and endeavors such as Cops Connecting with Kids and Coffee with a Cop, Bolin is more of a doer than a talker.

In an interview just days before Henderson’s annual Tri-Fest, Bolin said he always wants to be with visible and be with his officers. With law enforcement hosting a booth to raise money for the Cops Connecting with Kids program, he said he’d be there, too.

“HPD is selling doughnut burgers to raise money for that program,” he said. “I’m going to be helping in that booth. I’m kind of rolling up my sleeves and being involved.”

Bolin, who served as the Evansville Police Department chief for more than a decade, is no stranger to balancing the morale of the department with the trust of the community.

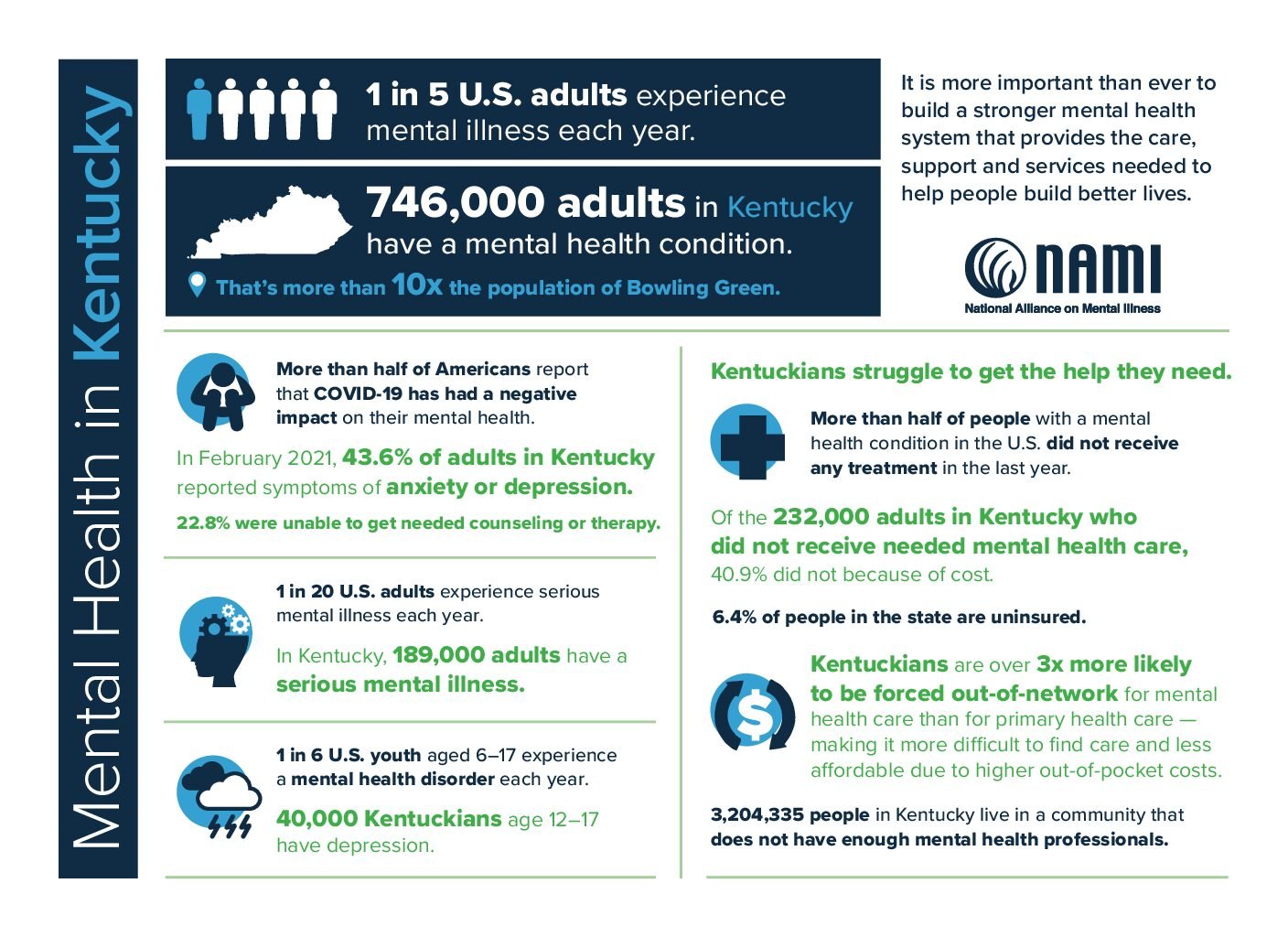

“I’ve been a police chief for a long time,” he said. “Every decision you make, not everybody is going to be happy with it. For our profession as a whole, morale is low. It’s not unique to Henderson.

Bolin said he intends to ride with officers during various shifts to learn more about policing in Henderson.

“I doubt I’ll stay an entire shift, but I do plan on hopping in a car with officers for a couple of hours to learn about who they are. I think when you’re in a car, on their turf, they’ll open up a little bit more than if they are in roll call around everybody else,” he said.

Bolin said HPD officers are very welcoming.

“They’ve been very nice. I hope I can keep that going,” he said. “Here I’m in the role if somebody needs correction, I have to give correction. If somebody needs discipline, I have to give discipline. Those are areas where you risk losing people, but you have to do these things or you lose the public.

“It’s a fine point,” he said. “I want to do those things in a way people respect and see I’m not doing it out of vindictiveness but that I’m trying to better the department and look out for the community. Hopefully, they’ll see that and understand it.”

Despite the past year when the department was losing officers to other nearby departments, Bolin said the HPD is solid—with good officers and good programs. Both retention and a lateral hiring plans that the Henderson City Commission approved under former Chief Sean McKinney seem to be paying dividends. Bolin said the department needs three more officers to be fully staffed.

“I’m not seeing anything we need to change” he said about HPD. “I think we’ve got a good department.”

Recruitment

As morale among law enforcement has taken a hit during the last several years, so has recruitment. Bolin, however, said there are several available avenues to improve recruitment – including a resource at Henderson County High School.

Retired HPD Officer Jermaine Poynter is launching several law enforcement classes in the 2024-2025 school year.

“The classes are Law Enforcement 1, Criminal Investigations and Forensics and Foundations of Justice and Public Safety,” Poynter said. “It’s an effort to steer more young people toward law enforcement careers.”

Bolin said the classes are good recruitment tools.

“This is a good place to start building those relationships, kind of setting that hook to get them interested in what we’re doing,” he said. “Then hopefully, they go off to college and stay interested in what we are doing (in law enforcement) or if they go in the workforce, they stay interested, and we see what we can do with them.”

Job fairs, college fairs and social media are all valuable platforms for recruiting potential law enforcement personnel.

Bolin said, however, the greatest recruiters are the police officers.

“We have to ingrain in our officers that the officers themselves are the biggest recruitment tool. If they go into a restaurant and have a young server who is doing a good job, just ask ‘Have you thought about being a police officer?’ They just plant that seed. People who may never have thought about law enforcement as a career, might start thinking about it then.”

While contented officers make great recruiters, those unhappy in their job can deter prospects, Bolin said. And that’s not beneficial in a career field that’s still battling a nationwide backlash. Many veteran cops don’t want their children to go into the profession, and it didn’t used to be that way, he said.

“That’s what we need to rebound from,” he said. “It seems in the past couple of years, it’s starting to smooth out. Maybe we are coming back around. Maybe this is again being viewed as a profession people want to be part of.”

Combating negative views of law enforcement takes a department committed to community policing.

“Departments need to be actively involved in community policing … being direct that we are a part of this community, and we aren’t different because we put on a badge and a gun. We want a safe community. We aren’t trying to kill people; we aren’t trying to hurt people. We want to help people. We are out here selling doughnut burgers; we’re taking your kids to Disney. We’re having coffee with you – the things where you aren’t taking someone to jail. We are being direct and trying to build relationships.

“I think that’s how you win people,” Bolin said. “I think in our profession as a whole, the bad has started to wake us up. I think you’re seeing this all over the country, that we have to change what we’ve done traditionally.”

Human resources for police and other first responders

If the plans of city officials hold true, Bolin won’t be the only newcomer working with law enforcement.

In a past interview with the Hendersonian, Henderson Mayor Brad Staton, said there are working plans to hire a human resource specialist who would act as a liaison between hazardous duty employees and city hall. The details are still being ironed out.

While new to HPD, Bolin is not new to the law enforcement culture and offered this advice to anyone cultivating a working relationship with police.

“I think it’s like I was saying with me. Right now, I’m an outsider. I’m the new person, so it’s being visible,” he said. “The more they see you, the more they talk to you, the more they feel they can trust you. “

He gave an example of a former chaplain for EPD who initially wasn’t connecting with officers. But he began volunteering to be the bad guy in SWAT training and then doing ride-alongs with officers.

“One by one, they’ve started to trust him,” he said. “So, I think it’s about being present. Listening and getting to know them. If we have a human resources specialist come in, that would be my advice. The more visible you are, the more you are around here, the more they’ll open up and trust you.”

Odds and ends

Bolin encountered some animosity with the Evansville F.O.P. when he received a vote of no confidence in 2019. Bolin, though, said that was par for the course with the F.O.P. in Evansville, saying the organization has a history of being combative to any chief of the police department. It was no different with him. “The fought me over everything,” he said.

He said he did ruffle feathers early on by changing the way EPD policed. There had been a history of the department being “heavy handed,” he said. EPD doesn’t use as much force as in the past, he said.

“When you change something that big early on you’re going to ruffle some feathers,” he said.

Former Evansville Mayor Lloyd Winnecke in a previous interview with the Hendersonian said Bolin was able to work through the FOP disagreement and to continue on with his priorities. He said he never doubted in 12 years that Bolin could lead the department.

“My confidence always grew with him,” Winnecke said.

But after Winnecke finished his third term, and new Mayor Stephanie Terry took over in Evansville, appointing one of Bolin’s best friends, Phil Smith, as the new police chief, Bolin believed his career in a uniform was over. And he was ready for that to be the case. He told people he never wanted to put on the uniform again. “I really meant it,” he said.

But then the Henderson chief’s job came open after McKinney resigned in late February and then Bolin began receiving numerous phone calls and messages.

“So many people blowing my phone up,” he said.

And he started to reconsider retirement.

Part of that came from a bit of nostalgia. Bolin started his career at HPD and was an officer here from 1995-1998.

“This is where I started,” he said, adding it seemed fitting to end his career where it had begun.

He said he cashed out his pension from his three years at HPD, thinking he’d never be back. He said he’s kicking himself for that now.

But he’s not chief yet. His current title is “police consultant” and becoming chief is dependent upon passing a certification test, which is most often used for new officers coming into police work. Much of the certification is physical, such as bench press, pushups and running.

When he was hired in mid-March, Bolin had 90 days to pass the Peace Officer Professional Standards certification.

Bolin said in his first 30 days he’d cleaned up his diet and lost 20 pounds but hadn’t yet reached the threshold for the 1 ½ mile run. “Getting my wind up is the problem,” he said, though added, “I’m confident I’m going to pass that (test).”

And after that, he plans to be chief at HPD at least five years, but has set a goal for 10. But no more.

“I don’t want to work in my 60s,” he said.

–Vince Tweddell contributed to this report.