(This article first appeared in the October print edition of the Hendersonian.)

After a visit to the base where her father was stationed in England during the Second World War, Susie Thurman told the manager of the museum there that she’d send him an email regarding all the letters her father had sent to her mother all those years ago when he was stationed at England’s Royal Air Force Burtonwood base.

She had no idea that the promise to delve into her father’s letters would go any farther than the email she promised. But then she started typing out the letters and then she typed more until she had a hefty page count.

“It just started as an email to him, and it grew,” Thurman said.

Talking to fellow writers online, she learned that she’d written too many pages for a typical memoir. The writers suggested a trilogy—each at the length more digestible to readers.

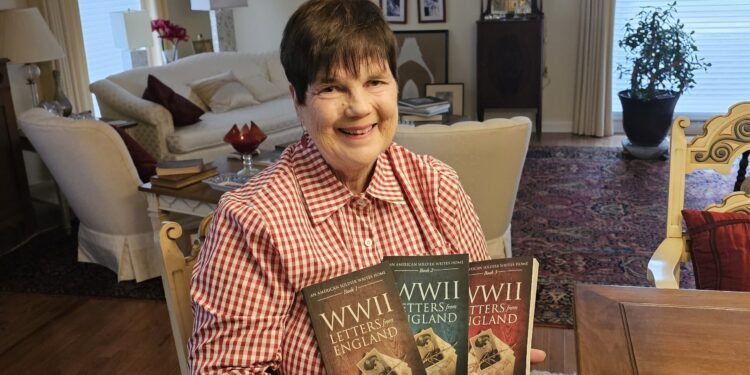

Now, six years after her first inkling to send an email about the letters, Thurman published in August the third installment of her trilogy, “WWII Letters from England: An American Soldier Writes Home.”

In the three-book series, Thurman has transcribed the 500-plus letters (with edits, context and historical data) that Charles “Muggins” Sommers sent to his wife, Catherine “Buzz” Sommers during the war. Muggins spent most of his time during the war on the Burtonwood base, and the letters paint the picture of his life there, from the work on the base to the trips taken to regional towns to the love he felt for his wife left behind in Henderson.

Muggins died in 1980, and at the time, Thurman didn’t know he’d written all those letters back to her mom. Some time later, her mom—“Buzz” was her nickname—mentioned the trove of letters stored in the basement. Still, Thurman shrugged at the letters and went on with her busy life teaching high school English back then.

Now, and especially as she’s worked on the trilogy, it’s one of her biggest regrets. For one, if she’d known about the letters and read them while Muggins was alive, he could have answered some of the questions that have come up as she worked on the books.

For two, if she’d been able to ask her mother about her father’s letters—and her response to them—that could have also answered so many questions and added dearly needed context to the back-and-forth. For the record, Buzz answered Muggins’ letters but he had nowhere to store them in his barracks and had to get rid of them.

Through the work, she got to know her father at an age before she was alive.

“He was here with me in his 30s,” she said of the time she was working on the book. “He was 42 when I was born. I got to discover an earlier version of him, and I liked the man I discovered.”

Thurman said, though, that he was still the same man; he’d not undergone some great transformation after she’d come along. He was just a younger version of the man she knew.

“Of course, I was a daddy’s girl and that remains,” she said.

She was also excited to happen upon some of the details of Muggins’ life then that now, years later, stand out. During his time post-war in England, he got the chance to attend a basketball officials training school in Paris. There, he learned the game from University of Colorado coach Forrest “Frosty” Cox and none other than the University of Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp. Both were in France to teach at the school, Thurman said.

Muggins also attended a concert in which a young girl wowed the crowd. It was Petula Clark, who two decades later would come to the United States and hit it big here, most notably with her most famous song, “Downtown.”

Thurman said she never knew Muggins had seen Clark in concert.

“All the time in the ’60s when I was listening to Petula Clark,” she said. “Of course, he probably wasn’t.”

Now that she’s finished the books, there are still a few tasks connected to the project. She wants to go through some of Muggins’ scrapbooks and send photos and programs that might be of interest to John Cotterill, who is the manager of the RAF Burtonwood Heritage Centre and the person to whom she said she’d send the email that to put the whole project in motion.

After that, she’ll be done. She said she’ll miss the work, the hours and hours poring over her father’s letters. It’s been rewarding, she said. Some of the reward has come from readers who tell her, “I’m so glad I got to know Muggins.”

Thurman also hopes to find other descendants of Americans whose father or grandfather served at Burtonwood. So far, she’s been unsuccessful.

In the end, it was a labor of love, for Muggins and for those he served with.

“I hope that I’ve given homage to him and the other people that were over there,” Thurman said.

***

Thurman will discuss her books and the letters—and probably much more—at a book signing at 6:30 p.m. Oct. 22 in the Henderson County Public Library event suite. Editor’s note: Thurman is a member of the board of West Kentucky Public Service Journalism, the nonprofit company that publishes the Hendersonian.