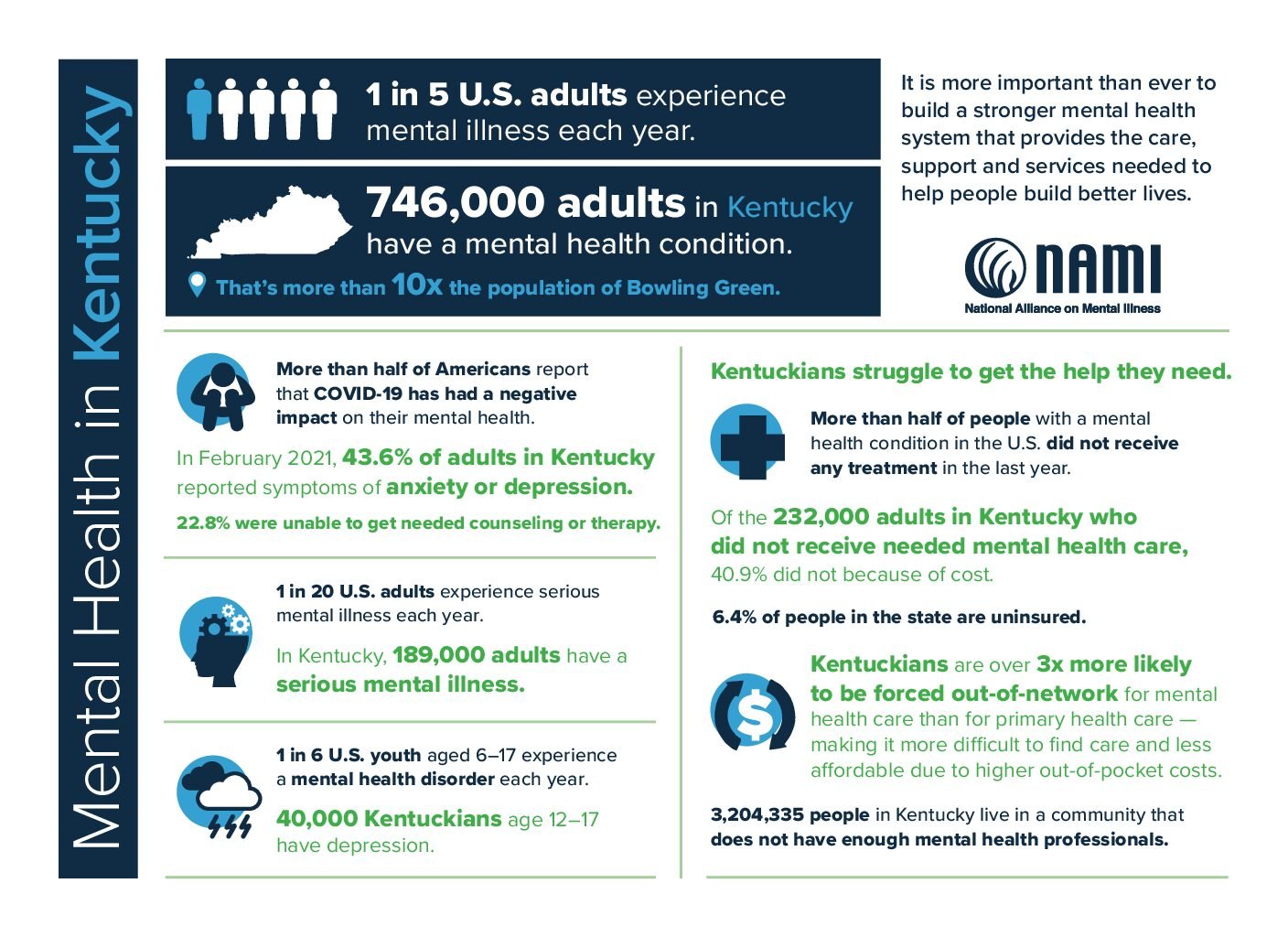

A downtown explosion in 1938 caused injuries and fatalities and its emotional aftershock indirectly led to an alienation of affection lawsuit and a divorce.

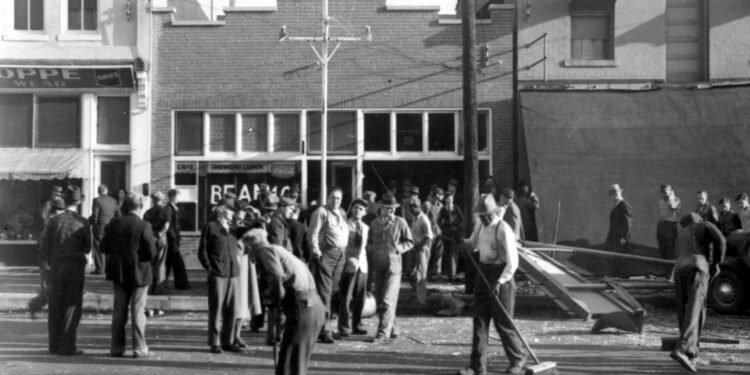

Louis T. Hoffman, 60, and his wife lived upstairs from their bar and liquor store, Hoffman’s Place, at 309 First St., which in recent decades has been occupied by Fast Print. At 6:55 a.m. on Nov. 12, 1938, he lit a match to light the furnace as he was preparing to open for the day.

He got considerably more heat and light than he was expecting, according to The Gleaner of Nov. 13: “The explosion blew out the front plate glass windows of the two-story brick building, knocked down two iron posts in front, allowing a shed that formed a marquee to collapse, and converted the interior of the store into a shambles….

“The Hoffman liquor store was virtually wrecked by the blast. Inside the floor was buckled, the tin ceiling was hanging in jagged pieces, and part of the liquor stock was overturned and broken. Upstairs … furniture was overturned, partitions were broken, and window shades were ripped to shreds. The entire front of the lower story was blown out, windows in the back were broken and part of one wall collapsed into an alley….

“A city employee who would not be quoted said he had warned Mr. Hoffman a month ago that gas was leaking into the building and that he should have his service lines checked.”

John Long, 60, a house painter, had been sitting on the running board of a truck in front of the bar. He was enveloped by flames and flying glass; he died a few minutes after being admitted to the hospital.

Long’s sister, Mrs. Fronie Rhodes, told The Gleaner that Long had been on his way to the Lyne Paint & Glass store but apparently stopped to talk with Joe Middleton, the janitor at the saloon.

Middleton, 51, had been sitting on the running board next to Long at the time of the blast. He was blown under the truck but survived with burns on his face and back.

“I was reading an article in the morning paper to Mr. Long when I heard a big roar,” Middleton said. “A flash blinded me, and something struck me in the back. I got up and started running and a policeman (E.G. Crowley) came up. I couldn’t see Long but when they put me in the ambulance I told them, ‘There are some people in that building and they need help.’”

Crowley had been sitting in the White Front café next door to the bar at the time of the blast. “I was showered with glass and ran into the street,” he testified at the inquest. “Middleton came running toward me asking for help. Then I saw Long lying partly under a truck parked in front of the liquor store. I picked him up and assisted him across the street.” Middleton sat on the curb, no doubt in some shock, until Crowley helped him into the Paul B. Moss Funeral Home ambulance when it arrived.

At that point, Crowley testified, he saw Hoffman coming out of an alley at the side of the bar; Hoffman got into the Moss ambulance without anyone’s assistance. Paris Jones, an employee of Moss, said Hoffman was horribly burned. “He said he wasn’t hurt much but skin was hanging from his hands when he got into the ambulance.”

Lucille Hoffman was still upstairs at the time of the blast, so she was mostly sheltered, although she was taken to the hospital for “nervous prostration” and a severe gash to her left leg.

She made it down the stairs without assistance but collapsed at the bar’s side door. Crowley and another officer, Ira Campbell, helped her into an ambulance.

Sherman Whitledge, manager of the Red Front store across the street, suffered a lacerated left hand when struck by flying glass. He looked out just in time to see the liquor store’s sidewalk shed collapse “and flames shoot from the shattered windows.”

The impact was felt over the entire community, but especially in the downtown area. Eight other businesses had their windows blown out or otherwise sustained damage; most of them had plate glass windows.

They included the White Front Café, the White Front grocery, the A&P grocery, Fitzgerald & Sons Furniture, the Fairway Store, the Red Front Master Market, Gibson’s Furniture Store, Kloke’s Auto Parts and the J.R. Davis liquor store.

“Within a few minutes after the blast, (three) ambulances and fire trucks rushed to the scene and wild rumors swept the city during the excitement. Many residents believed there had been an earthquake and telephone exchange switchboards became clogged with calls.”

Little hope was held for the survival of Louis Hoffman. The bar’s proprietor was badly burned about the head and upper part of his body. He died at the hospital 16 hours after the explosion.

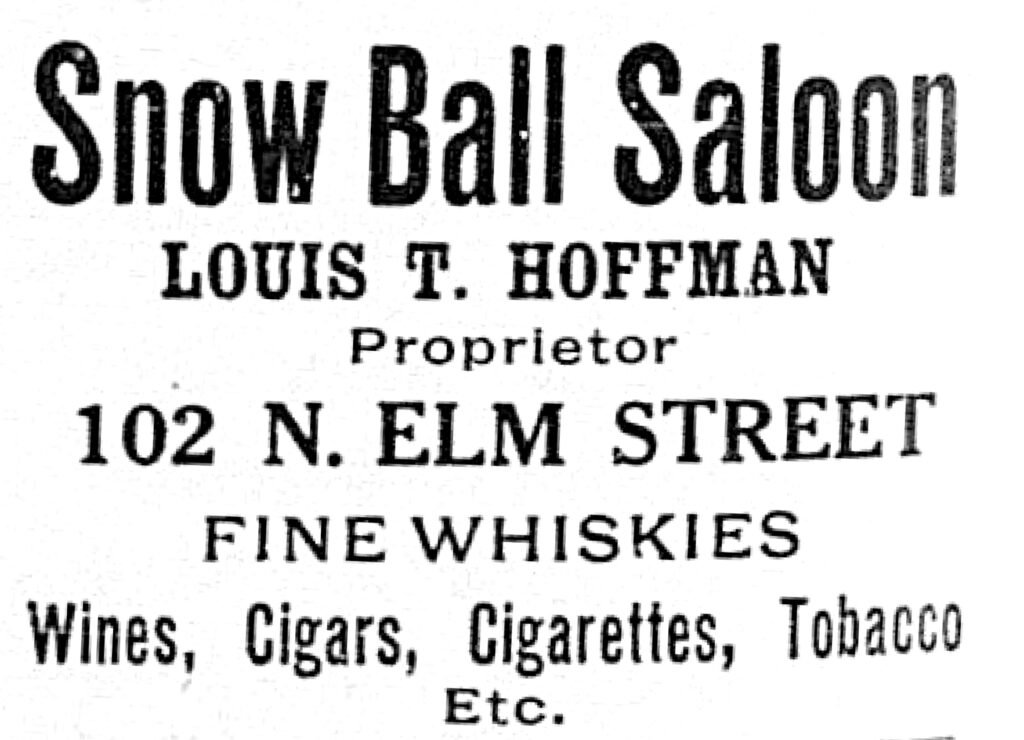

He had entered the tavern trade as early as 1909. He was listed in that year’s city directory as bartender for N.R. Dill. Three years later he was working at a bar at 101 N. Main St., and possibly was the proprietor of it. The 1915 city directory reports he owned the Snow Ball Saloon at 102 N. Elm St. When Prohibition came along, he switched to soft drinks, and opened a restaurant at 309 First St., which later became Hoffman’s Place.

Lucille Hoffman, who was about two decades younger than her husband, stayed in the hospital a few days and then went to the house of her mother-in-law at 857 Madison St. That’s when the aftershock began rumbling.

Across the street at 901 Madison St. lived Louis L. and Queenie Smith, who were Lucille’s brother- and sister-in-law.

Exactly what went down is disputed, but on June 17, 1939, an alienation of affection lawsuit against Lucille Hoffman was filed by Queenie Smith, who claimed Lucille, after being widowed in the gas explosion, was trying to steal her husband.

After Lucille got out of the hospital, the suit claimed, she went to her mother-in-law’s house where she began “in a systematic way by blandishments and flattery and furnishing him money, to attract and to entice plaintiff’s husband to herself” during her 10-day stay there.

She then supposedly “inveigled” Louis to accompany her to Owensboro in April 1938, where they spent several nights under assumed names. They then went on to Louisville, where they continued their scandalous conduct.

And the kicker, Queenie alleged, was a trip through the western states, apparently trying to stay in Nevada long enough for Louis to qualify for a quickie divorce. She asked for $25,000 damages.

Lucille’s answer, filed by her attorney, denied each and every one of those claims, and asked that the case be dismissed.

That’s exactly what happened, although the details aren’t in the case file. A settlement was reached out of court and the case was dismissed Sept. 18, 1939.

However, details of the settlement are included in Queenie’s deposition in her divorce suit, which she filed against Louis Sept. 8, 1939. In Queenie’s deposition taken Aug. 26, 1940, she said Lucille Hoffman paid her $1,500 to settle the alienation of affection suit.

So, there may have been some justification to Queenie’s allegations, especially considering Louis and Lucille married Aug. 4, 1941, which was about five weeks after the divorce was finalized June 27, 1941. It was the second marriage for both of them.

Louis and Queenie had married in 1919 and separated in April 1939—about the same time he had gone off with Lucille on their scandalous cross-country trip.

According to Queenie, the marriage was not a happy one. Except for a period of about four months, he had been drunk for most of the 12 years before they separated, she said. Furthermore, he occasionally had struck her when drunk, but mostly she stayed out of his way.

She worked at the family-owned Fernwood Floral Shoppe to support herself. Louis also occasionally worked there, according to the deposition of his first cousin, Blanche Troutman, a nurse who was friends with Queenie.

“He worked when they were first married but he hasn’t worked for the last 10 or 12 years. He dabbled around the greenhouse there when he sobered up, and when he did work they were scared to have him go out. He would collect the money and spend it for liquor.”

Both Queenie and Blanche testified he was in the county jail at the time of their depositions, and had been there for public intoxication numerous times during the previous 12 years.

The marriage of Louis and Lucille apparently didn’t last long. There is no local divorce case on file, but the 1944 city directory shows he was living with his stepmother at 857 Madison St. and working as an upholsterer, while she lived at 106 S. Alves St. and worked at the Public Welfare Office.

Louis L. Smith married for a third time in 1950 but had no wife when he died Aug. 21, 1966, in Miami, Florida, according to his obituary in The Gleaner.