Defending Heroes Project continues the work; Gala will be Saturday, May 18

(This article first appeared in the May print edition published April 30)

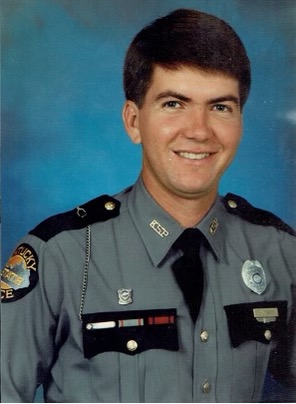

Former Henderson resident Floyd Hunsaker was just months out of the Kentucky State Police academy when he was dispatched to a call that changed everything.

A graduate of Henderson County High School, Hunsaker – who was 23 years old on Jan. 4, 1983 – responded to Glomarw Hollow in Perry County to assist in serving an arrest warrant.

The hours that unfolded thereafter became the deadliest shootout in Kentucky State Police history.

“I was shot four times,” Hunsaker said. “Back in those days there wasn’t psychological therapy” for traumatic experiences.

“We had a chaplain, and he was a nice guy,” Hunsaker said. “He approached it from a religious standpoint, which is fine. But he didn’t tell me that you’re going to have nightmares. With loud noises, you are going to be startled for a long time. These were things I went through but wasn’t really understanding the reactions myself.”

Suck it up. Let’s go have a beer.

Forty years after Hunsaker was shot, there are more resources and a little less stigma for emergency responders and veterans needing to process trauma.

In September 2022, veteran Henderson Police Department Officer Joe Whitledge launched the Defending Heroes Project which now networks with other similar entities throughout the nation and in several countries, including Canada, Israel and the United Kingdom.

The Defending Heroes Project tries to bridge the gap between a first responder and the help they might need—anything from financial assistance during medical and other types of emergencies to mental health resources. Sometimes the offering is as simple as a conversation among comrades.

“I saw the need with first responders and veterans,” Whitledge said. “We go through things on the job and might need a hand up or support.”

(The organization is holding a gala from 7 to 11 p.m. May 18 at the Owensboro Convention Center. More on that later.)

“When you start out as an officer, you get, ‘Suck it up. Don’t show emotion’ or ‘Suck it up. Let’s go have a beer,’ ” the Henderson officer said. “I’d say it’s just been within the last four or five years that people have started talking about Post Traumatic Stress in relation to law enforcement and other first responders.”

Whitledge said first responders often don’t share facts about their experiences with their families.

“You don’t want to go home and tell your family that you worked a call with an infant that you performed CPR on, and the baby didn’t make it, or that I had a gun pointed at me, and I almost didn’t come home. Instead, you say, ‘Oh nothing happened on shift.’ You don’t tell them.

“The worst moments of someone’s life, amounts to five or six times a month or more for a first responder,” Whitledge said. “The average person experiences two or three traumatic events in a lifetime. A first responder experiences on average five per month. In a 25-year career, you’re looking at more than 900 traumatic events.”

Projecting strength is as important to first responders as demonstrating skill in emergency situations, he said.

“You don’t want to say anything and be looked at as weak or unable to do your job.”

Here’s the problem: That adrenaline and stress must go somewhere, he said.

“There is more loss of first responders to suicide then being killed in the line of duty,” he said. “There were 158 suicides among first responders in the nation in 2023.”

Whitledge describes the fight or flight adrenaline that surges in first responders as equivalent to being on a fast-moving train.

“It’s like the train is going … you go to the suicide call; you go to the child injured or death call … they are traumatic. You box it up and put it away and go to the next call which could be something serious or non-traumatic. You go through ups and downs throughout just one shift.

“But you put it up and go to the next thing and don’t process the ugliness,” he said. “If you don’t sort out those traumas, then you’re 10 to 15 years in and things happen like with COVID and everything was shut down … people were isolated. It could be that the emergency responder retires. The train may stop, but all that trauma and the weight of those experiences keeps coming, and it’s going to slam into you.”

Focusing on the mental health of emergency responders “has come a long way,” Whitledge said. “But there’s a generational mentality of how trauma has always been handled by first responders and veterans. We have to break that.”

Whitledge said the mental well-being of first responders will in turn provide better care to the community.

“A first responder with good mental health is going to affect everyone,” he said. “If you’ve got an officer whose mental health is taken care of, they’ve processed things versus an officer who is burned out or who hasn’t processed trauma and is stuck in fight or flight, that will affect how you do your job. If you’ve processed it, and you’ve decompressed it, you can focus on the job, and it benefits everyone. We are really trying to address mental health.”

A KSP pioneer

If anyone can appreciate the challenges surrounding first responders and mental health, it’s Hunsaker.

Following the shooting, Hunsaker spent nearly a year recovering physically before returning to active duty. It took longer for him to recover emotionally.

“I was off duty for eight to nine months. I had to have surgeries and physical therapies. I got shot in the arm, wrist, shoulder, and left hand. I had to do all kinds of physical therapy.

“I finally got cleared to return to work,” Hunsaker said. “I had put in a transfer to go to the Henderson post from Hazard County. I didn’t have relatives and only a few friends in Hazard, so I didn’t want to go there. But the state police said I had to go back. I ended up staying there for three or four years.”

Hunsaker was studying psychology at Western Kentucky University when he joined the state police. After the shooting, he sent a memo to the then state police commissioner encouraging the agency to develop an employee assistance program which would help troopers work through traumatic experiences.

“I knew we needed something,” he said. “The memo sat there, and no one did anything with it. I left the state police and started working for the FBI. And two or three commissioners later, the new KSP commissioner was looking through all the recommendations people had submitted over the years and found mine. He thought it was a good idea.”

Around 1990, Hunsaker—who now has a bachelor’s degree in psychology, a master’s degree in counseling, another master’s degree in marriage and family therapy and a doctorate in counseling—was stationed in the FBI field office in Omaha, Nebraska, when the state police reached out asking him to return to the agency to develop an employee assistance program.

Thanks to Hunsaker, the state police mandated that any trooper involved in a shooting must have at least one therapy session with him.

Until the 1990s and the implementation of the mandatory therapy session, no one discussed what a trooper would feel when seeing or experiencing traumatic events.

“It was just part of the job,” Hunsaker said. “It was seen as weak if it bothered you. So, what happens? The affected officer internalizes it. And most start drinking. Drowning their sorrows or doing other high-risk behaviors like having affairs or doing all kinds of crazy things. And that’s their minds trying to cope with the experience, but in an unhealthy way.

“Something else we were told is that you just have to forget about it and move on. In my therapy sessions, I would tell people, ‘No, you need to think about it or talk about it. Take one hour a day and think about the traumatic experience. Get angry, cry, everything. Then after that hour, get up, and go do something else. You kind of flood yourself with emotions for that one hour. You do that every day for two or three weeks, and you’re taking control of your emotions, they aren’t taking control of you. You decide when you want to deal with it.”

Hunsaker had a lot of credibility with the troopers who came to see him.

“None of them could say that I don’t know what it’s like,” he said. “Yes, I do. It took me two years to get over it.”

Glomawr Hollow, 1983

“We were serving a warrant on Tommy Allan Combs who was on federal parole. He’d been in prison twice. This would be his third arrest, and if convicted, he’d go away for life,” Hunsaker recalled. “He knew we were coming for him, and he told his neighbors, ‘I’m going to take as many with me as I can. The first one through the door, I’m going to blow his head off.’ None of the neighbors warned us.”

Five state police troopers and three Perry County sheriff’s deputies assembled in Glomawr Hollow to serve the warrant.

“It’s a two-story house that had been turned into two separate residences, but it looked like one house. So, we surrounded the house … a guy came out, and we knew it wasn’t Combs. He wouldn’t tell us where Combs was. But when he came out, someone shut the door behind him, and we knew then someone else was in the house,” he said.

Hunsaker said a state trooper and a Perry County deputy banged on the door, identifying themselves as law enforcement.

“No one answered, so they kicked the door in. Combs is inside the house, off to the side about 10 feet away from the door. He’s at an angle, armed with a rifle and a pistol. When the officers kicked the door in, he unloaded his weapons into them. He killed the deputy right away. The dead deputy falls into the house, while the state trooper, who was also shot, falls backward onto the porch. He’d been shot two or three times,” Hunsaker said.

Meanwhile, two people—a woman and a 14-year-old—decide to leave one of the residences and the teen is hit by crossfire and is killed, he said.

“Combs comes out on the porch, and he’s standing over the trooper he has just shot, and he’s getting ready to shoot him in the head,” Hunsaker said. “That’s when I first saw Combs. I have my mini 14 rifle, and I start shooting. I shot 14 times, and I hit him about six or seven times in the right shoulder and chest. He dropped his gun on the porch and went back into the house.

“Combs was about 400 pounds,” Hunsaker said. “He was so big and thick, those rounds might have been fatal, but they didn’t kill him right away. So, he picks up the shotgun of the deputy he’s just killed, looked out the window, and sees who’s shooting at him. That’s when he shoots me, and I fall.

“There’s a little apple tree where I fell. I put my head against the apple tree. He’s still shooting at me, and I knew he might hit my arms, but he’s not going to hit my head.”

When the bullets ripped into Hunsaker, he said, “It felt like he blew both of my arms off. Both of my hands were numb. I couldn’t feel anything with any of my fingers. I was lying there helpless. I thought he’d run out of the house and put a bullet right through my head.”

While trying to survive the barrage of bullets, the injured trooper who was still on the porch implored Hunsaker to help him.

“He’s begging me to come get him saying, ‘I’m dying! I’m dying!’ He didn’t know I’d been shot. I yelled back, ‘I can’t! I can’t move!’”

Combs is still shooting at Hunsaker, when the injured trooper on the porch picks up his shotgun and fires at Combs, striking him. Combs died in the living room.

The trooper who fired that final shot, “is paralyzed for life. I’ve got four bullet holes in me” and three are dead.

Hunsaker said he had to lay where he was for about another 45 minutes until the scene was cleared.

“I didn’t know if I was going to get out alive.”

A new day

Hunsaker not only survived the ordeal but used it to blaze a trail toward more help for other first responders. Whitledge is doing something similar with the Defending Heroes Project and its upcoming Hometown Heroes Bash on Saturday.

Ticket prices are $85 per ticket or $640 per table. People can sponsor tables or sponsor an item for raffles or live auctions. There are several items, including Caribbean trips, jewelry, grilling utensils and gift cards being auctioned.

“Last year we had almost 400 people attend,” Whitledge said. “This year, we are looking at around 500.”

Proceeds from last year’s gala and donations from community partners help first responders and veterans locally, as well as across the nation.

Connecting people to mental health support is just one facet of the outreach conducted by the Defending Heroes Project.

In Henderson, the organization paid the medical bills of an HPD officer battling cancer.

In Louisville, a police officer and his wife are struggling due to their youngest child’s medical expenses. The 1-year-old has been diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer, Whitledge said.

“LPD has been great, and the officer has had paid time off. His wife has unpaid time off through FMLA. They have two other children who are just slightly older than the baby. The officer told me that with their limited finances, ‘I’m just trying to keep our house and her car.’”

Thanks to donations to the Defending Heroes Project, Whitledge was able to give the Louisville police officer and his family a check to help alleviate financial stress.

“I left there feeling so awesome to be a part of that,” Whitledge said. “I immediately messaged the supporters to let them know of what they’ve been a part.”

In Illinois, the DHP is assisting Illinois State troopers in getting one of their own to Austin, Texas, for a specialized treatment. The Illinois trooper, Brain Frank, suffered a traumatic brain injury when his cruiser was struck by another vehicle, Whitledge said.

“The trooper and his family have battled workman’s comp for three years,” he said. “They’ve had to raise money on their own to get him to Austin for a two-week treatment. Defending Heroes Project is helping to cover some of the family’s living expenses while another organization is covering travel costs so the trooper can receive treatment for his head injury.”

Whitledge said “from coast to coast” the Defending Heroes Project is trying to “fill in the gap, anywhere we can.” “In a lot of these situations, individuals and family feel like they’re on their own or they don’t have the support,” he said. “I think for first responders and veterans all over the country, organizations like the Defending Heroes Project helps them feel like they aren’t alone.”

For more information about tickets to the Hometown Heroes Bash or resources available through the Defending Heroes Project contact Whitledge at 270-860-7081 or email Defendingheroesproject@gmail.com.