(This article first appeared in the August print edition of the Hendersonian.)

“Well, I’ve been out walking

I don’t do that much talking these days

These days

These days I seem to think a lot

About the things that I forgot to do for you

And all the times I had the chance to…”

Though written by Jackson Browne, “These Days” was recorded by Glen Campbell and seems an apt opening to a story on music and how it affects those with dementia/Alzheimer’s. “I’ll be Me,” a particularly poignant and effective documentary on Glen Campbell, his farewell tour, and his journey with Alzheimer’s, is a must watch. What stays with the viewer is that though Campbell struggled with the rigors of the disease, and the memory and often, lyrics, stolen from him, his hands never forgot the chords of his music and the rhythmic connection to his loyal fans.

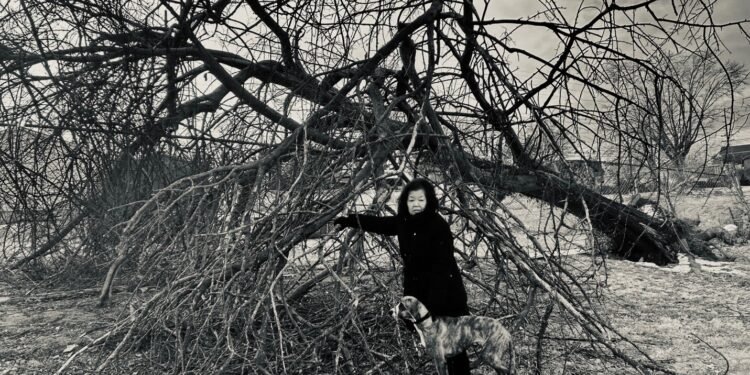

I watched “I’ll be Me” with my mother two summers ago. We were working long days outside together to set up my small farm. She was the young age of 86 and still able to work arduously in the sun, putting fences together with me, lifting heavy bags of soil; later bent over in that soil, I planted vegetables, while she stuck to planting flowers (some that silently rankled, as I didn’t approve of their pinky color.) At night, we would make a huge dinner and watch a movie, usually a documentary. (I often watch documentaries over narrative films as working in the film industry has left me wanting for reality rather than fiction.) I don’t know if she was truly aware of her dementia diagnosis then, and it didn’t really matter. The throughline of the film is universal and underlines the importance of the human gift for connection, no matter the disease.

Another favorite documentary was the “Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones,” in which her mother country, Okinawa, was featured. By watching this together, I had hoped it would inspire her, watching Okinawans older than her, working the land, farming, dancing, singing and thriving.

I remember my mother watching quietly, perhaps unaware of her diagnosis and its connection to memory loss. She was moving her head and hands to the traditional songs being sung in the film and singing each word under her breath, though it had been some fifty-nine years since she had sung them in Okinawa prior to moving to the United States.

One dark still morning that summer, we sat in sacred silence having our coffee. The birdsong hadn’t yet begun, and her words had a particular timbre: resonant, full of weight, memorable.

“Did you hear that song last night? I could hear it from my bed. I just want to know if you heard it too.”

“No Mom, it’s dead quiet here. I couldn’t hear anything.”

“Well, I did,” she insisted. “It went something like this.”

She began humming a traditional Okinawan song, a few words beginning to fill the spaces. It sounded like something out of a music box: a tune one equates with a wordless lullaby, or a song played in the music boxes of my own childhood, where a plastic ballerina with a smeared visage and hard donut bun twirls on one extended leg with faded painted pointe shoe, narrowly in step with the tune. This song has been brought up from time to time during the past five years of the dementia journey, sometimes I will admit, with my own disbelief creeping in, followed by a sighing acceptance. And yet as someone along for the long hard ride of this journey, parallel, standing shoulder to shoulder with her on the road, just what if the connection to this song were real? What if we could manifest a particular piece of music, for memory’s sake, to accompany us on the difficult path? What if there were a parallel universe, where we are not only connected to the past via memory, but when and if that memory fails us, the connective tissue still forms a physical bond—a balm that sang us to sleep as a child and perhaps still does the same for us as an adult? With dementia, all lines are blurred—not only for the person living with it, but also for the caregiver.

At a memory café recently, I was paired with an elderly couple to learn to play the bells. The songbook was simple enough, seemingly written for a child, the bells corresponding to colors and numbers. As someone overly aware that I am not adept at reading, this was a relief for me. The three of us went through the book, playing a few songs, mostly successfully. The last song, oddly enough, induced tension. The gentleman, the one with dementia, kept faltering and was aware that he “wasn’t playing the song correctly.” With each mistake, his wife simply had him begin again. Before the final exercise, she quietly nudged, “Remember, you introduced this song to me.

You sang it to me when we met…” With that, he played the bells to perfection, smiling, not even looking at the songbook, a moment from the past, as well as his self, recaptured.

This morning, I sat in the wee hours at dawn, coffee cup to my lips. Looking outwards past the shadows of the cherry tree, remembering the familiar darkness, making out which plants were growing, which I had neglected and were a wash. Out of the corner of my eye, a fantastical pink form, and out of focus star, catching the first light. The insistent showy flowers planted two years prior, when memory clung steadfast and the sun warmed all summer. My mother’s pink flowers, pink for a girl, pink for a life filled with happiness. I swear I could hear the Japanese lullaby myself, whispered quietly, a memory, a real time moment perhaps, just before dawn.