(This article first appeared in the November print edition of the Hendersonian.)

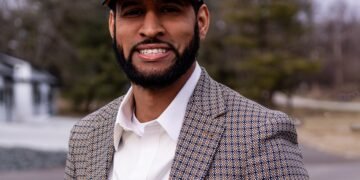

Local landowners who have signed a lease with Cordelio Energy, Jim and Holly Vincent, say that hosting a wind turbine on their land makes sense in a number of ways.

Among the reasons they gave for signing the lease, two main points emerged during a recent conversation with the Hendersonian.

For one, the world—and Henderson County—is demanding more energy.

Two, if Henderson County doesn’t have energy, then it will get left behind, said Holly Vincent. That means that industry that would look to the county to locate could end up going someplace else with a greater ability to provide the energy needed to run its business, causing the county to lose jobs.

Jim Vincent said that Henderson County has railways, highways and the river—all conducive to further development. “We need energy,” he said.

But there are other more personal reasons that Holly and Jim Vincent have signed a lease. There are financial considerations. Both are retired and the money coming from payments from Cordelio and from a solar company—they have leased land to solar in the county, too—enhances their financial security.

“It helps,” Jim Vincent said.

What’s more, the Vincents rent much of their several parcels of land to farmers, and Holly Vincent explained that though that income is relatively consistent, there can still be a bad year. A lease for a wind turbine on a piece of land offers some security, while leasing solar panels offers more than what they can get from farming, they say.

The leases are also transferable so that it becomes a legacy investment in their family, they say. The Vincents have four adult-age sons.

Beyond their own concerns, there are reasons they feel that leasing for wind turbines is a good idea. For one, the land for which they’ve signed the lease for windmills is 209 acres of farmland on the Green River and in the flood plain in a very sparsely populated area of the county, which is a piece of land suited for a turbine, they say.

“The whole farm is in a flood plain,” Jim Vincent said.

Additionally, the property tax rates increased significantly on the land they leased to the solar company after solar panels were installed, they said. Though they still own the leased land, they only pay taxes on the assessed value of the home and land before the solar panels were put on it. The solar company pays taxes on the difference between the assessed value of the property pre-solar panels and the property post-solar panels, a sum that is a tax benefit to the county government—more than half of which goes to local public schools, they say.

“I don’t think (solar companies) have done a good job of (explaining) the tax benefits off solar,” Holly Vincent said.

Most landowners who have signed leases for windmills on their property have been drowned out by the passion of those opposing a windmill farm in Henderson County, including the group Henderson County Concerned Citizens-HC3.

That was evident at the Henderson City-County Planning Commission meeting on Sept. 2, when that body heard public comment about a proposed one-year moratorium on wind energy systems applications. More than two dozen community members spoke that evening. Only two spoke in favor of wind energy systems. Holly Vincent was one.

She contends those opposing wind energy systems are spreading a lot of misinformation as well as a “the sky is falling” mentality.

“I don’t think a turbine blade is going to twist off and fall off and hit my house,” she said.

“I’ve not found any studies (that show) you die from turbines,” she said, adding not like those found from the detrimental effects of coal and gas. “You don’t have that with turbines.”

Additionally, she said most of those opposed—at least in the public hearing—did not support their concerns. “They’re just saying they don’t want it,” she said. If someone only says, “I don’t want this—that’s not valid.”

Holly Vincent also believes that a push from HC-3 and others for regulations that limit a turbine’s height to 200 feet and include a mile setback from a turbine to a neighbor’s property are not objective.

One of the couple’s big objections is the length of the recently passed two-year moratorium. That’s delaying studies needed so that the process can continue, which is also a delay of finding where exactly wind turbines can be located in the county—bird and Native American artifact and archaeological and a host of other studies must be completed before the company can know where wind turbines can be placed.

“They want answers … that can’t be given yet,” Holly Vincent said.

Finally, perhaps the most important point for consideration in what could decide the type of local ordinance that is passed: Opponents say that windmills would devalue their property and that a landowner’s property rights end when what is done on the land negatively affects their land. Holly Vincent doesn’t see it that way.

“I don’t feel they have the right to tell me what I want to do on my own farm,” she said.